A Critical Review: Government Funding for Native American Housing Development Projects

Product Name: Federal Funding Mechanisms for Native American Housing Development

Category: Public Policy & Social Investment

Target Users: Native American Tribes, Tribal Designated Housing Entities (TDHEs), Federal Government agencies (HUD, BIA, IHS), Policymakers, Advocates

Price: Varies (Annual Congressional Appropriations)

Overall Rating: ★★★☆☆ (3.5/5 stars – Essential, but deeply flawed and underperforming)

Introduction: The Unmet Promise of Home

In the heart of the world’s wealthiest nation, a stark reality persists: Native American communities face some of the most severe housing crises in the United States. Substandard housing, overcrowding, lack of basic infrastructure, and homelessness are not isolated incidents but systemic issues rooted in historical injustices and chronic underinvestment. For decades, the federal government has acknowledged a trust responsibility to Native nations, including the provision of safe and adequate housing. This review examines the "product" designed to address this challenge: the various federal funding mechanisms for Native American housing development.

Treating government funding as a "product" allows us to analyze its features, performance, benefits, drawbacks, and overall value proposition, much like any consumer good. While invaluable and often the sole lifeline for many tribal housing initiatives, this "product" is far from perfect. It operates within a complex ecosystem of historical trauma, unique legal frameworks, and persistent socio-economic disparities. Our aim is to provide an in-depth, 1200-word analysis, dissecting its strengths and weaknesses, and ultimately offering a "purchase recommendation" – a blueprint for improvement – to better serve the housing needs of Native American communities.

Product Overview: A Patchwork of Programs

The primary federal "product" for Native American housing is the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA) of 1996. This landmark legislation fundamentally reshaped federal housing assistance to tribes, moving away from direct federal management towards a block grant system that empowers tribes with greater control and flexibility. Administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), NAHASDA provides grants directly to tribes or their Tribally Designated Housing Entities (TDHEs) based on a formula.

Beyond NAHASDA, other federal programs play supplementary roles:

- Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Program: While not exclusively for Native Americans, some tribes access CDBG funds for housing-related infrastructure and community development.

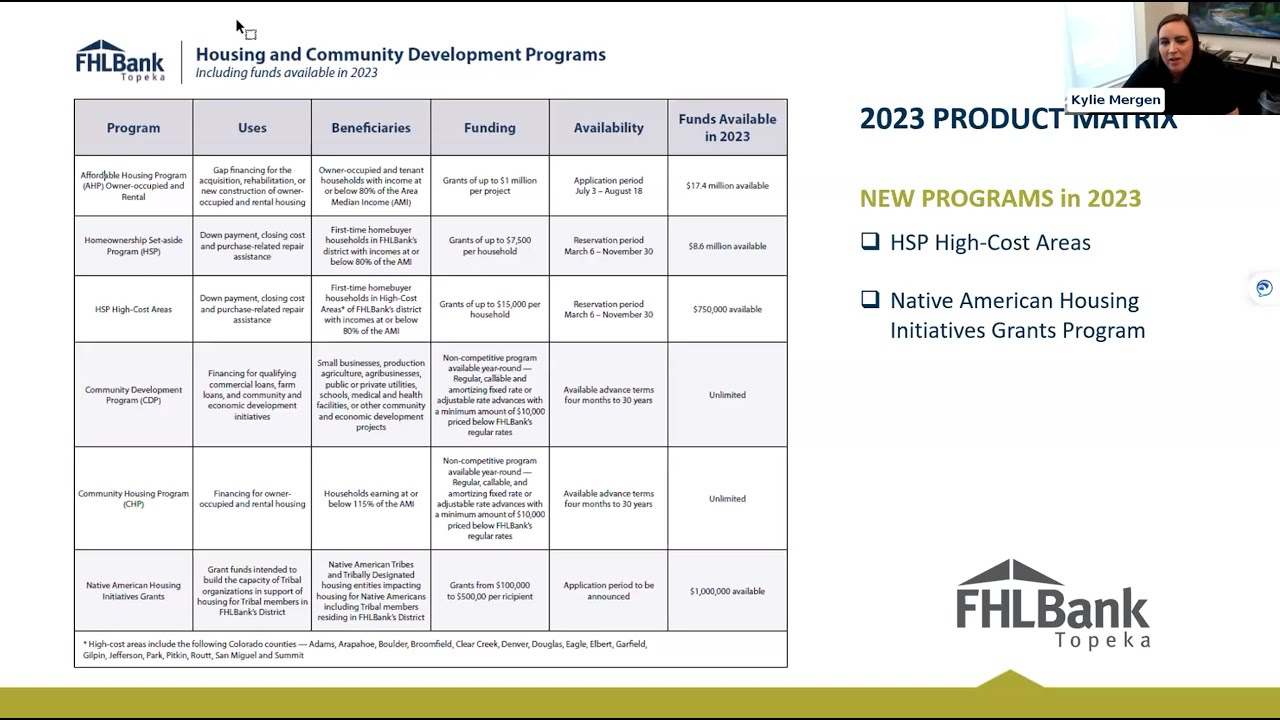

- Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC): A critical tool for affordable housing development nationwide, LIHTC can be leveraged by tribes and TDHEs, often in conjunction with NAHASDA funds, to attract private investment.

- Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA): Historically involved in housing, the BIA now primarily focuses on infrastructure support (e.g., roads) that indirectly impacts housing development.

- Indian Health Service (IHS): Critical for water and sanitation infrastructure, IHS programs are essential for ensuring new housing units are habitable.

- Department of Agriculture (USDA) Rural Development: Offers housing loans and grants in rural areas, which can include tribal lands.

The core "feature" of this federal funding "product" is its intent to address a severe national crisis while respecting tribal sovereignty. It represents a commitment, albeit often an insufficient one, to rectify historical wrongs and support self-determination in housing.

Key Features & How It Works: The NAHASDA Model

NAHASDA is the cornerstone, representing the federal government’s most direct and flexible approach to tribal housing. Its key features include:

- Block Grant System: Instead of categorical programs with strict federal oversight, NAHASDA provides lump-sum funds. This empowers tribes to identify their specific housing needs and priorities, and then allocate funds accordingly.

- Tribal Self-Determination: Tribes and TDHEs develop their own Indian Housing Plans (IHPs) which outline how they will use NAHASDA funds. This local control is paramount, allowing for culturally appropriate housing solutions.

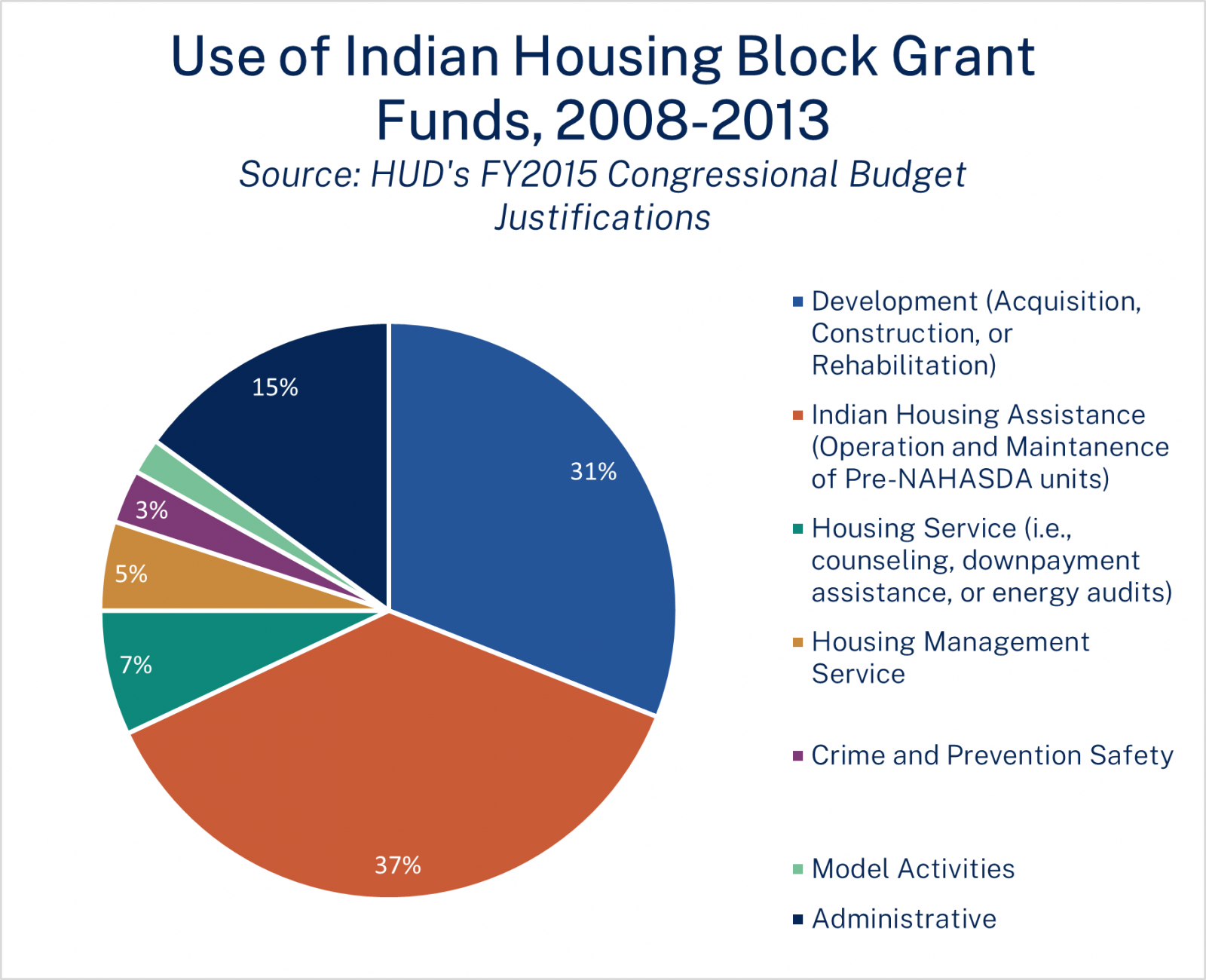

- Flexible Use of Funds: NAHASDA funds can be used for a wide range of activities, including:

- Development, acquisition, and rehabilitation of affordable housing.

- Housing services (e.g., housing counseling, energy audits, tenant services).

- Rental assistance.

- Crime prevention and safety activities.

- Model activities (innovative approaches to housing).

- Infrastructure development directly related to housing (e.g., water, sewer lines to new homes).

- Affordability Focus: Funds are primarily targeted at low-income Native American families.

- Formula-Based Allocation: Funds are distributed based on a formula that considers factors like the number of low-income households, housing conditions, and population.

This framework was a significant advancement, designed to be more responsive and respectful of tribal governance than previous federal housing programs.

The Pros: Strengths of Government Funding (Our "Product’s" Advantages)

Despite its shortcomings, federal funding for Native American housing development offers several critical advantages:

- Addresses Critical Needs: The most fundamental benefit is that these funds provide basic shelter and improve living conditions for thousands of Native American families. Without this funding, the housing crisis would be immeasurably worse, leading to increased health disparities, educational disadvantages, and social instability.

- Promotes Tribal Self-Determination: NAHASDA’s block grant structure is a powerful tool for self-governance. Tribes are no longer passive recipients but active designers and implementers of their housing solutions. This fosters local capacity, culturally appropriate designs, and programs tailored to unique community needs.

- Economic Development Catalyst: Housing development projects create jobs, stimulate local economies, and build tribal enterprises. Construction, material sourcing, and ongoing maintenance generate income and skills within the community, fostering economic self-sufficiency.

- Infrastructure Development: While often insufficient, NAHASDA and complementary programs (like IHS sanitation facilities) enable the development of essential infrastructure – water, sewer, and electricity lines – which are prerequisites for habitable housing, especially in remote areas.

- Leverages Other Funds: NAHASDA funds often serve as critical seed money or matching funds, allowing tribes to access other funding sources like LIHTC, USDA loans, or private financing. This leveraging effect multiplies the impact of federal dollars.

- Improved Health and Well-being: Access to safe, stable, and healthy housing directly correlates with improved physical and mental health outcomes, reduced childhood illnesses, better educational attainment, and a higher quality of life.

- Cultural Preservation: With tribal control, housing can be designed to reflect and respect cultural traditions, architectural styles, and community living patterns, reinforcing cultural identity and well-being.

In essence, this "product" is a vital and often irreplaceable resource that has enabled significant, albeit insufficient, progress in addressing the severe housing challenges faced by Native American communities.

The Cons: Weaknesses and Challenges (Our "Product’s" Flaws)

While essential, federal funding for Native American housing is plagued by significant weaknesses that hinder its effectiveness and prevent it from fully resolving the crisis:

- Chronic Underfunding: This is the most pervasive and debilitating flaw. NAHASDA’s funding levels have never been adequate to meet the immense needs, and in real terms, have often declined since its inception. The gap between available resources and the estimated cost of addressing the housing backlog on tribal lands is staggering, leading to perpetual waiting lists and continued substandard conditions.

- Bureaucratic Hurdles and Red Tape: Despite the intent of self-determination, tribes still face significant administrative burdens, complex reporting requirements, and lengthy application processes across various federal agencies. This can be particularly challenging for smaller tribes with limited administrative capacity.

- Infrastructure Deficits Remain Severe: While some funds can address infrastructure, the sheer scale of the need for basic utilities (water, sewer, electricity, broadband) in remote tribal communities often far outstrips available housing funds. Without this foundational infrastructure, building new homes is impossible or prohibitively expensive.

- Capacity Challenges: Many tribes, especially smaller ones, struggle with limited human and technical capacity to plan, develop, and manage complex housing projects, or to navigate the intricate web of federal regulations and funding opportunities.

- Political Volatility: Annual appropriations mean that funding levels are subject to political whims, making long-term planning difficult and creating uncertainty for tribal housing authorities.

- Restrictive Regulations (Despite Flexibility): While NAHASDA offers flexibility, other federal regulations (e.g., environmental reviews, labor standards like Davis-Bacon Act) can add significant costs and delays, especially in unique tribal contexts where local solutions might be more efficient.

- Data Gaps and Inconsistent Metrics: A lack of comprehensive, up-to-date data on tribal housing conditions and needs makes it difficult to accurately assess the problem, allocate funds equitably, and measure program impact effectively.

- Inter-Agency Coordination Failures: The siloed nature of federal agencies (HUD, BIA, IHS, USDA) often leads to fragmented efforts. A tribe might secure housing funds from HUD but struggle to get timely infrastructure support from IHS or BIA, stalling projects for years.

- Land Tenure and Jurisdictional Issues: Unique trust land status, fractionalized ownership, and complex jurisdictional boundaries can complicate financing, property rights, and project development on tribal lands, often increasing costs and timelines.

- Sustainability Challenges: Building new homes is only part of the solution. Long-term maintenance, energy efficiency, and operational costs for housing units can strain tribal budgets, especially in areas with extreme climates. Funding for these aspects is often insufficient.

These weaknesses collectively undermine the "product’s" potential, creating a cycle where progress is slow, incremental, and often fails to keep pace with the growing demand.

Performance and Value for Money

Considering the extreme need, the "performance" of federal funding is a mixed bag. Where funds are allocated, they invariably lead to tangible improvements in people’s lives. Families move out of dilapidated structures into safe homes, children perform better in school, and communities gain a sense of stability. The "value for money" is high in terms of the human impact and the fulfillment of a federal trust responsibility.

However, the "performance" is severely hampered by the "product’s" flaws. The chronic underfunding means that the scale of the crisis is not being adequately addressed. The bureaucratic hurdles mean that efficiency is often compromised. While each dollar spent provides immense value to the recipient, the overall system is not optimized to deliver comprehensive, scalable solutions effectively. It’s like having a high-quality, essential tool that is only intermittently powered and frequently bogged down by unnecessary friction.

Who is this "Product" For?

This "product" is primarily for Native American tribes and their designated housing entities (TDHEs) seeking to develop, rehabilitate, or manage affordable housing for their members. It is also for the federal government to fulfill its legal and moral trust responsibility to Native nations. Ultimately, it is for every Native American individual and family striving for a safe, healthy, and culturally appropriate place to call home.

Recommendation: Improving the "Product" (Our "Purchase Recommendation")

To truly address the Native American housing crisis and elevate the "performance" of federal funding, a fundamental overhaul and renewed commitment are required. Our "purchase recommendation" is not to abandon this essential "product," but to invest heavily in its upgrade and optimization:

- Substantial and Sustained Funding Increases: This is the absolute priority. NAHASDA funding must be significantly increased, indexed to inflation and actual need, and made mandatory rather than discretionary. A multi-year commitment would allow for long-term planning and more ambitious projects.

- Streamline Bureaucracy and Enhance True Flexibility: Reduce redundant reporting, simplify application processes across agencies, and empower tribes with even greater discretion on how funds are used, within broad parameters. Trust tribal nations to know their needs best.

- Dedicated Infrastructure Funding: Create a separate, robust, and coordinated federal fund specifically for critical housing-related infrastructure (water, sewer, electricity, broadband) on tribal lands. This fund should be accessible to tribes directly and work seamlessly with housing development programs.

- Invest in Tribal Capacity Building: Provide ongoing technical assistance, training, and resources to help tribes and TDHEs develop expertise in project management, financial planning, grant writing, and sustainable housing practices.

- Improve Data Collection and Evaluation: Fund comprehensive, tribal-led housing needs assessments and develop consistent, culturally relevant metrics to track progress and demonstrate impact, ensuring data-driven policy decisions.

- Foster True Inter-Agency Collaboration: Mandate and facilitate seamless coordination between HUD, BIA, IHS, USDA, and other relevant agencies. Create a "one-stop shop" or integrated planning framework for tribes seeking housing and infrastructure support.

- Promote Sustainable and Culturally Appropriate Designs: Encourage and fund the development of energy-efficient, climate-resilient, and culturally informed housing solutions that reduce long-term operating costs and reflect tribal values.

- Address Unique Challenges: Develop targeted programs or set-asides for tribes facing unique challenges, such as those with extremely remote locations, limited land bases, or severe historical underdevelopment.

- Leverage and Expand Innovative Financing: Expand access to LIHTC and other private sector financing tools for tribal projects, and explore new models for attracting capital to tribal housing initiatives.

- Prioritize Housing as a Human Right: Reframe the federal approach to tribal housing not just as a program, but as a fundamental aspect of upholding human rights and fulfilling treaty obligations.

Conclusion: A Foundation for Justice and Self-Determination

Federal funding for Native American housing development is a necessary, life-changing "product" that has demonstrably improved countless lives and upheld, to varying degrees, the principle of tribal self-determination. However, its current iteration is severely hampered by chronic underfunding, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and a fragmented approach to complex, interconnected needs.

The "purchase recommendation" is clear: the federal government must dramatically increase its investment, streamline its processes, and adopt a truly holistic, collaborative, and tribally-driven strategy. Without a fully upgraded and optimized "product," the promise of safe, adequate, and culturally appropriate housing for all Native American communities will remain an elusive dream. It is not merely an investment in bricks and mortar, but an investment in health, education, economic opportunity, and the enduring sovereignty of Native nations. The time for incremental adjustments is over; a bold, transformative commitment is long overdue.