Navigating the Path to Homeownership: An In-Depth Review of Employment History Requirements for Tribal Housing Loans

Homeownership stands as a cornerstone of financial stability, wealth creation, and community development. For Indigenous peoples across the United States, this aspiration is often interwoven with unique cultural, historical, and economic contexts. Federal programs like the Section 184 Indian Home Loan Guarantee Program, along with tribal housing initiatives and other USDA/HUD programs, aim to bridge the gap in access to capital for Native Americans and Alaska Natives seeking to purchase, construct, or rehabilitate homes on trust land, restricted land, or in approved areas. A critical component, and often a point of both flexibility and friction in these loan applications, is the assessment of employment history.

This article provides an in-depth review of "Employment History for Tribal Housing Loans" as a critical product—a set of requirements and interpretive guidelines—that significantly impacts a tribal member’s ability to secure financing. We will explore its inherent advantages and disadvantages, culminating in recommendations for optimizing this essential process to better serve the unique financial realities of Indigenous communities.

Understanding the "Product": Employment History in Tribal Lending

At its core, the employment history requirement in any lending scenario serves as a primary indicator of a borrower’s capacity and willingness to repay a loan. Lenders scrutinize a borrower’s work record to assess income stability, consistency, and future earning potential. For conventional loans, this often translates to a straightforward review of W-2s, pay stubs, and tax returns, typically looking for two years of stable employment in the same field or with upward mobility.

However, the "product" of employment history requirements for tribal housing loans is designed, or at least intended, to be more nuanced. Recognizing the distinct economic landscapes within Indian Country – which often include seasonal employment, traditional economies, self-employment, remote work, and varying levels of formal documentation – these programs attempt to offer flexibility. The goal is to balance the lender’s need for risk mitigation with the unique circumstances of tribal members, ensuring that culturally relevant and economically viable income sources are recognized.

Key aspects of this "product" include:

- Standard W-2 Employment: For those with conventional jobs, the process mirrors mainstream lending, requiring pay stubs, W-2s, and verification of employment.

- Self-Employment & Contract Work: Common in many tribal communities (e.g., artists, crafters, consultants, tradespeople). Lenders typically require two years of tax returns (Schedule C) to demonstrate consistent income.

- Seasonal Employment: Prevalent in industries like fishing, forestry, tourism, and agriculture. Lenders may accept letters from employers, a history of re-employment, or a combination of income sources to establish a consistent annual earning pattern.

- Traditional Income Sources: Income from traditional arts, crafts, subsistence activities (e.g., commercial fishing, hunting guide services) may be considered, often requiring detailed documentation and explanations.

- Tribal Per Capita Payments: Payments derived from tribal enterprises (casinos, natural resources) can sometimes be considered as qualifying income, provided they are consistent, documented, and expected to continue. Policies vary significantly by lender and program regarding their inclusion.

- Income from Trust Assets: Income from trust land leases, mineral rights, or other tribally held assets may be considered if verifiable and stable.

- Education and Training: Recent graduates or individuals completing vocational training may have their future earning potential considered if they have secured employment in their field.

The effectiveness of this "product" hinges on its implementation by individual lenders, the borrower’s ability to document their unique income streams, and the overarching federal guidelines that govern these specialized loan programs.

Advantages of the Employment History Requirements for Tribal Housing Loans

When effectively applied, the employment history requirements for tribal housing loans offer several significant advantages for borrowers, lenders, and tribal communities alike:

-

Risk Mitigation for Lenders: The primary benefit for lenders is the ability to assess a borrower’s capacity to repay. By evaluating past income, stability, and work patterns, lenders can make more informed decisions, reducing the risk of default. This ensures the long-term viability of the loan programs themselves, encouraging continued investment in tribal housing.

-

Increased Access to Capital for Tribal Members: Unlike conventional loans that might rigidly exclude certain income types, the flexibility built into tribal housing loan programs (especially Section 184) allows for the consideration of diverse income streams common in Indigenous communities. This is a crucial advantage, as it broadens the pool of eligible borrowers who might otherwise be shut out of the mainstream mortgage market due to non-traditional employment.

-

Recognition of Diverse Economic Realities: This "product" acknowledges that the economic landscape in Indian Country is not monolithic and often differs significantly from urban or suburban economies. By accepting documentation for seasonal work, self-employment in traditional arts, or per capita payments, the requirements demonstrate a vital understanding of and respect for tribal economic sovereignty and cultural practices.

-

Promotes Financial Literacy and Documentation: The process of compiling and documenting employment history, particularly for non-traditional income, encourages borrowers to develop better financial record-keeping habits. This can empower individuals with greater financial literacy and control over their economic data, benefiting them beyond the loan application process.

-

Supports Self-Sufficiency and Economic Development: By facilitating homeownership, these requirements indirectly support tribal self-sufficiency. Homeowners contribute to the local economy, build equity, and create stable environments, which are essential for broader economic development within tribal nations. The ability to leverage diverse income sources for home loans can also stimulate local economies by supporting small businesses and traditional trades.

-

Tailored Underwriting Flexibility: Programs like Section 184 specifically train lenders and underwriters on the unique aspects of tribal lending. This specialized knowledge allows for more nuanced and flexible underwriting decisions that consider the holistic financial picture of a tribal applicant, rather than applying a rigid, one-size-fits-all approach. This tailored approach is a significant "feature" of the product.

-

Empowerment through Homeownership: Ultimately, the advantage lies in achieving the goal: homeownership. By providing a pathway for tribal members to qualify for loans based on their actual economic contributions and realities, the employment history requirements serve as a tool for empowerment, enabling individuals and families to build assets and secure their future.

Disadvantages of the Employment History Requirements for Tribal Housing Loans

Despite their intended flexibility, the employment history requirements for tribal housing loans also present several disadvantages and challenges:

-

Documentation Burden for Non-Traditional Income: While flexible in theory, documenting non-traditional income can be incredibly burdensome for borrowers. Self-employed artists, seasonal workers, or those relying on fluctuating per capita payments may not have readily available pay stubs or W-2s. Compiling two years of detailed records (bank statements, invoices, letters from buyers, tribal resolutions for per capita) can be time-consuming, confusing, and overwhelming, acting as a significant barrier.

-

Inconsistent Lender Interpretation and Lack of Expertise: A major drawback is the inconsistent application and interpretation of these flexible guidelines by different lenders. Not all lenders or loan officers are equally trained or experienced in tribal lending. Some may default to conventional, rigid underwriting standards, misinterpreting or simply refusing to accept legitimate, non-traditional income sources. This leads to frustrating and often arbitrary rejections for otherwise creditworthy applicants.

-

Challenges for Seasonal and Gig Economy Workers: Even with allowances, seasonal work inherently presents challenges in demonstrating "stable" income. Gaps in employment or significant fluctuations can raise red flags for underwriters, regardless of a proven history of re-employment or a consistent annual income. The rise of the gig economy further complicates this, as sporadic income streams can be difficult to project and verify.

-

Limited Opportunities in Remote Tribal Areas: Many tribal lands are located in remote, rural areas with limited formal employment opportunities. The reliance on traditional economies, subsistence activities, or small, community-based enterprises means that a stable, W-2 "job" might simply not exist for many residents. Even with flexible guidelines, the sheer lack of conventional employment options remains a fundamental barrier.

-

Per Capita Payment Restrictions and Volatility: While per capita payments can be considered income, lenders often apply strict rules regarding their consistency and future outlook. If payments are not guaranteed to continue for at least three years, or if they fluctuate significantly, lenders may exclude them entirely or only count a conservative average. This can disproportionately affect tribal members whose primary or supplementary income comes from these distributions.

-

Risk of Bias and Cultural Misunderstanding: If not handled with extreme sensitivity and cultural competence, the evaluation of non-traditional employment can inadvertently introduce bias. Lenders unfamiliar with tribal economic structures might undervalue or dismiss legitimate income sources due to a lack of understanding, perpetuating systemic disadvantages.

-

"Credit Invisibles" and Lack of Formal Credit History: While not strictly about employment, the challenge of proving consistent income is often linked to the broader issue of "credit invisibles" in Indian Country. Many tribal members may have a limited formal credit history due to cash-based economies or a reliance on tribal or community lending. Without a strong formal credit score, lenders lean even more heavily on employment history, exacerbating the documentation burden.

-

Time Delays and Frustration: The increased documentation requirements and the potential need for extensive communication between borrowers, tribal authorities, and lenders to clarify income sources can lead to significant delays in the loan application process. This extended timeline can be a source of immense frustration for applicants, sometimes leading them to abandon the pursuit of homeownership.

Recommendations for Optimizing the "Product"

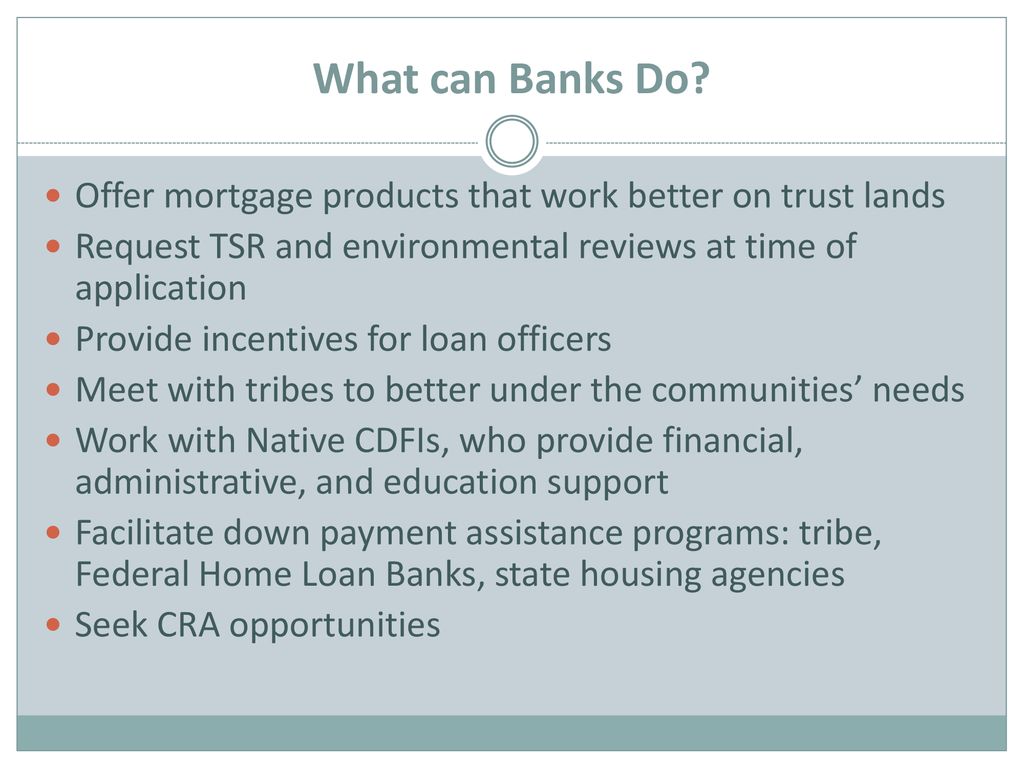

To enhance the effectiveness and equity of employment history requirements for tribal housing loans, a multi-faceted approach involving lenders, policymakers, tribal nations, and borrowers is essential:

-

Mandatory Cultural Competency Training for Lenders: All lenders participating in tribal housing loan programs should undergo mandatory, recurring training specifically focused on Indigenous cultures, tribal economies, and the unique aspects of underwriting in Indian Country. This training should emphasize the interpretation of non-traditional income sources, the value of tribal verification letters, and best practices for engaging with tribal members.

-

Standardized, Clearer Guidelines for Non-Traditional Income: Federal agencies (HUD, USDA) should work with tribal leaders and lending experts to develop clearer, more standardized, yet flexible guidelines for documenting and accepting non-traditional, seasonal, self-employed, and per capita income. This could include templates for tribal income verification letters, standardized calculation methods for seasonal income, and specific examples of acceptable documentation.

-

Promote and Support Tribal Financial Counseling and Housing Services: Tribal housing authorities and other tribal organizations are uniquely positioned to assist members. Increased funding and support for these entities to provide pre-purchase counseling, financial literacy education, and assistance with compiling loan documentation (especially for complex income histories) would be invaluable. This could include workshops on record-keeping for self-employed individuals or those with seasonal income.

-

Leverage Technology for Documentation and Verification: Explore and implement technological solutions that streamline the documentation process. This could include secure online portals for submitting and verifying documents, or platforms that help borrowers compile a comprehensive financial history from various sources (e.g., bank statements, tribal payment records).

-

Holistic Underwriting Approach: Encourage and incentivize lenders to adopt a truly holistic underwriting approach that considers the borrower’s entire financial picture, community ties, and demonstrated ability to manage finances, rather than solely relying on rigid employment history metrics. This could include consideration of on-time rent payments, utility bill payments, and tribal loan repayment histories.

-

Develop Specialized Loan Products and Pilots: Explore the creation of pilot programs or specialized loan products designed specifically for unique tribal economic situations. For instance, loans tailored for artists with fluctuating sales, or programs that offer more innovative ways to secure loans for those with strong community support but less formal employment history.

-

Advocacy for Policy Amendments: Tribal nations, advocacy groups, and lenders should continue to advocate for policy amendments that further refine and adapt federal loan programs to better fit the realities of Indigenous communities, ensuring that the spirit of flexibility is consistently translated into practice.

-

Borrower Education and Preparation: Empower tribal members with knowledge. Educational initiatives should inform potential borrowers about the documentation required for various income types, the importance of consistent record-keeping, and how to effectively communicate their unique financial situation to lenders. Early engagement with housing counselors can significantly improve readiness.

Conclusion

The "product" of employment history requirements for tribal housing loans is a complex and evolving mechanism. When implemented with understanding, flexibility, and cultural competence, it serves as a powerful enabler of homeownership and economic empowerment within Indigenous communities, acknowledging and respecting the diverse ways tribal members contribute to their economies. It mitigates risk for lenders while opening doors to capital for those who might otherwise be excluded.

However, the current iteration of this "product" is not without its flaws. Inconsistent application, a heavy documentation burden for non-traditional incomes, and a lack of universal lender expertise often transform its intended flexibility into a frustrating and exclusionary barrier. The disadvantages highlight a critical need for continuous refinement, better training, and a more culturally informed approach to lending in Indian Country.

Ultimately, the recommendation is not to discard the requirement for employment history, as it remains a vital tool for responsible lending. Instead, the recommendation is for a comprehensive and concerted effort to refine and consistently apply this "product" through enhanced education, clearer guidelines, technological support, and a steadfast commitment to cultural competence. By doing so, we can ensure that the path to homeownership for tribal members is truly accessible, equitable, and reflective of their unique and resilient economic realities, thereby fulfilling the promise of these vital housing loan programs.