A Deep Dive into Native American Housing Programs: A Co-Housing Perspective

Product Name: Native American Housing Programs (A Framework for Community-Centric Living)

Category: Community & Sustainable Housing Solutions

Reviewed By:

Date: October 26, 2023

Executive Summary: A Unique Offering with Specific Gateways

For individuals captivated by the ethos of co-housing – shared values, community support, sustainability, and intergenerational living – Native American housing programs present a fascinating, albeit complex, case study. While not a "product" in the conventional sense that one can simply "purchase" or "join" off-the-shelf, these programs represent a deeply rooted, culturally informed approach to communal living that often embodies the very principles co-housing advocates seek.

This review will explore Native American housing programs through the lens of co-housing, examining their inherent advantages, the significant limitations for those outside tribal membership, and ultimately, who this "product" is truly for. Our recommendation for non-Native individuals interested in co-housing is to view these programs as a profound source of inspiration and a model of community resilience, rather than a direct pathway for participation, unless specific, rare circumstances apply.

Introduction: The Allure of Co-Housing and Indigenous Roots

The modern co-housing movement, with its emphasis on intentional community, shared resources, and a balance of private and communal spaces, has gained significant traction. People are seeking alternatives to isolated suburban living, yearning for connection, mutual support, and a more sustainable lifestyle. It’s a pursuit of belonging, a desire to live in harmony with neighbors and the environment.

Ironically, many of these "modern" ideals have been cornerstones of Indigenous communities for millennia. Native American housing programs, primarily administered by Tribal Housing Authorities under the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA), are designed to provide safe, affordable, and culturally appropriate housing for enrolled tribal members. While their primary goal isn’t to create a "co-housing development" in the Western sense, their inherent structure, cultural values, and focus on community often align remarkably with the aspirations of co-housing enthusiasts.

This article will treat "Native American Housing Programs" as a conceptual "product" – a system or framework – to evaluate its merits and drawbacks for an individual interested in co-housing, recognizing that access is fundamentally tied to tribal affiliation and sovereignty.

What Are Native American Housing Programs?

At their core, Native American housing programs are mechanisms for self-determination in housing, primarily funded through federal block grants (NAHASDA) and administered by over 400 Tribally Designated Housing Entities (TDHEs) or Tribal Housing Authorities. These programs aim to:

- Provide Affordable Housing: Address the severe housing shortages and substandard conditions prevalent in many Native American communities.

- Promote Self-Sufficiency: Offer homeownership opportunities, rental assistance, and housing rehabilitation.

- Support Cultural Preservation: Design and develop housing that reflects tribal traditions, values, and architectural styles where appropriate.

- Foster Community Development: Integrate housing with broader community infrastructure, services, and economic development goals.

Crucially, these programs operate on sovereign tribal lands, governed by tribal laws and customs, and are primarily intended to serve enrolled members of the respective tribes. This foundational principle is the most significant differentiating factor when considering these programs through a co-housing lens for a general audience.

The "Co-Housing" Appeal: Where Values Intersect

For someone drawn to co-housing, the underlying values and practical manifestations of many Native American communities present a compelling parallel:

- Strong Community Bonds: Indigenous cultures are inherently communal. Concepts of mutual aid, collective well-being, and extended family networks are foundational. This translates into housing arrangements where neighbors often function as a supportive network, sharing responsibilities and celebrating together.

- Intergenerational Living: Many Native American communities prioritize the presence and wisdom of elders and the nurturing of youth. Housing designs or community layouts often facilitate intergenerational interaction, a key feature in many co-housing models seeking to bridge age gaps.

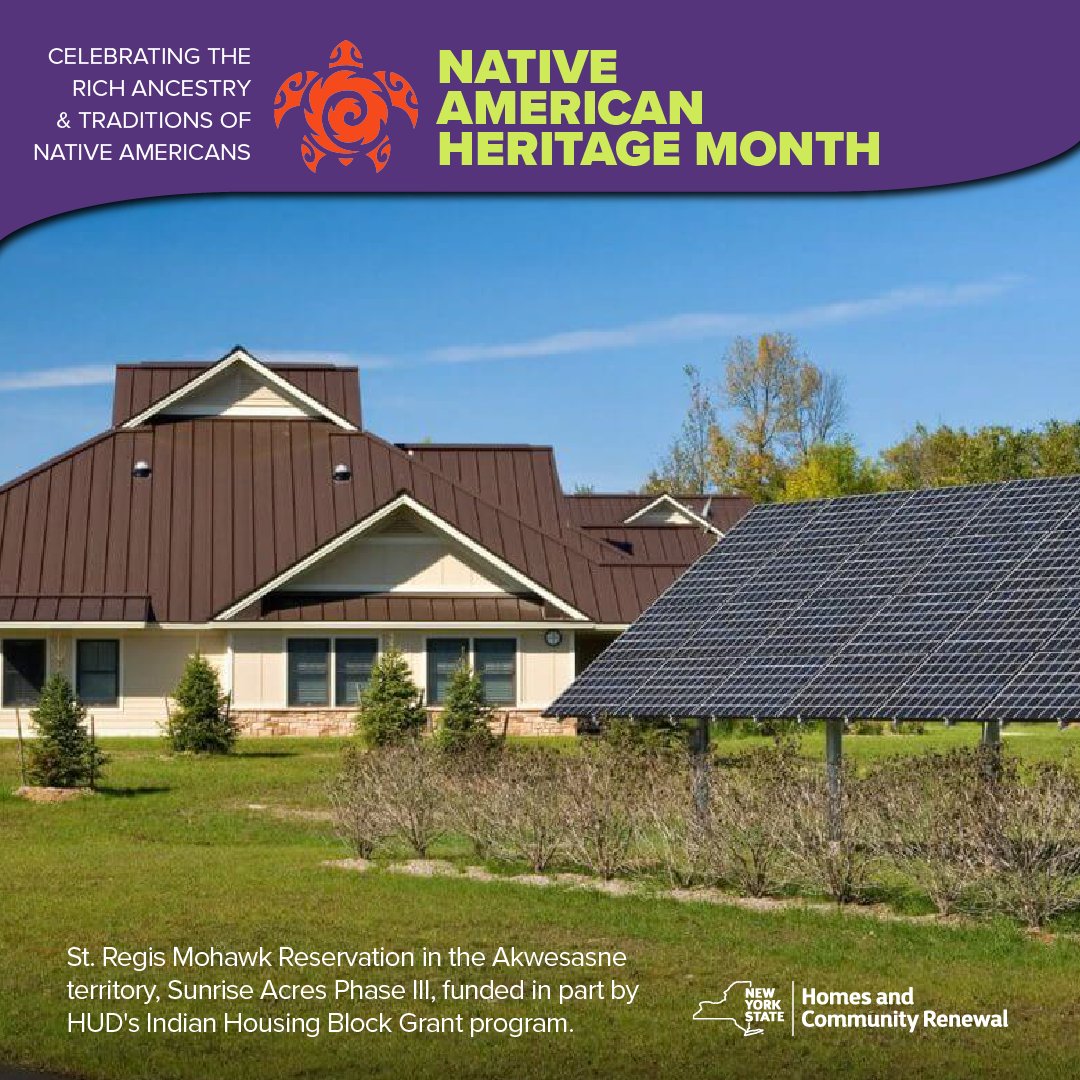

- Sustainability and Land Stewardship: Traditional ecological knowledge and a deep connection to the land are central to Indigenous worldviews. Housing programs often incorporate sustainable building practices, energy efficiency, and a respect for the local environment that aligns perfectly with eco-conscious co-housing initiatives.

- Cultural Preservation and Identity: Housing is not just shelter; it’s an expression of identity. Many tribal housing initiatives strive to incorporate traditional aesthetics, materials, and community planning principles that reinforce cultural continuity, offering a sense of shared heritage and purpose.

- Shared Resources and Spaces (Implicitly): While not always formalized as a "common house" in the Western co-housing sense, tribal communities often have shared community centers, cultural spaces, gardens, and land used collectively for ceremonies, hunting, or gathering. The concept of shared responsibility for the collective good is paramount.

Advantages (Kelebihan) for the Co-Housing Enthusiast

If one could hypothetically access these programs, the advantages would be substantial, particularly for those deeply committed to co-housing principles:

- Pre-Existing, Deeply Rooted Community: Unlike new co-housing developments that must actively build community from scratch, many Native American communities possess centuries of shared history, values, and social structures. This provides an immediate, robust sense of belonging.

- Authentic Cultural Immersion: For those genuinely interested in a diverse, culturally rich living experience, these communities offer an unparalleled opportunity to learn from and participate in vibrant Indigenous cultures, languages, and traditions (respectfully, and if welcomed).

- Emphasis on Collective Well-being: The focus often extends beyond individual prosperity to the health and welfare of the entire community, aligning with co-housing ideals of mutual support, childcare, elder care, and shared responsibilities.

- Sustainable Living and Land Connection: Many programs incorporate traditional wisdom and modern green building techniques, fostering a deep connection to the land and promoting environmentally responsible living.

- Intergenerational Support Systems: The presence of extended families and community networks provides built-in support for all age groups, reducing isolation and enhancing quality of life for children and elders alike.

- Sovereignty and Self-Determination: Living within a sovereign nation offers a unique legal and political context, fostering a sense of self-governance and community control over local affairs.

- Affordability: A core mission of NAHASDA is to provide affordable housing, which is often a major draw for co-housing residents seeking to reduce living costs.

Disadvantages (Kekurangan) and Significant Barriers

Here, the "product review" hits a fundamental and critical wall for most individuals:

- Eligibility (The Primary Barrier): This is the single largest disadvantage. Native American housing programs are overwhelmingly designed for and restricted to enrolled members of a federally recognized tribe. For a non-Native individual interested in co-housing, this program is almost entirely inaccessible as a direct "solution."

- Why: These programs are an exercise in tribal self-determination and a fulfillment of the federal government’s trust responsibility to Native nations, aiming to redress historical injustices and support tribal communities. They are not public housing programs open to all.

- Sovereignty and Jurisdiction: Living on tribal lands means operating under tribal laws, governance, and customs, which can differ significantly from state or federal laws. While an "advantage" for self-determination, it can be a complex adjustment for outsiders unfamiliar with tribal legal systems.

- Geographic Remoteness and Infrastructure: Many tribal lands are located in rural or remote areas, potentially far from urban centers, employment opportunities, and certain amenities. Infrastructure (internet, roads, utilities) can sometimes be less developed than in non-tribal areas.

- Limited Availability: Even for eligible tribal members, the demand for housing often far outstrips supply. There are chronic housing shortages on many reservations, making new units or vacancies scarce.

- Cultural Differences and Integration Challenges: For the rare non-Native individual who might gain access (e.g., through marriage to a tribal member or specific employment that necessitates living on the reservation), genuine integration requires profound respect, humility, and a willingness to learn and adapt to cultural norms. Misunderstandings can arise without this deep cultural competency.

- Bureaucracy and Program Specificity: Navigating the specific rules, applications, and requirements of individual Tribal Housing Authorities can be complex, varying significantly from one tribe to another.

- No "Opt-in" for Co-Housing Principles: While many communities embody co-housing values, they are not typically structured as formal co-housing developments with elected committees, explicit shared meal schedules, or pre-defined common facilities for all residents in the Western sense. The communal aspect is often organic and culturally embedded rather than institutionally designed.

Who is this "Product" For? (Target Audience)

Primary Audience (Ideal Fit):

- Enrolled members of a federally recognized Native American tribe who are seeking affordable, culturally relevant, and community-oriented housing on their ancestral lands. These programs are explicitly designed for them and represent a vital resource for cultural continuity and community development.

Secondary Audience (Extremely Limited and Indirect Access):

- Non-Native individuals married to or in a committed relationship with an enrolled tribal member who is eligible for tribal housing. Even then, eligibility rules vary, and the non-Native partner would likely be living within the tribal member’s allocated housing, not directly accessing the program themselves.

- Individuals employed by a tribal government or enterprise in a capacity that requires them to reside on tribal lands, and where tribal housing is provided as part of their employment package. These are typically temporary or conditional arrangements.

- Academics or researchers engaged in specific, tribally-approved projects who may receive temporary housing on tribal lands.

Not For (Directly):

- General non-Native individuals simply looking for a co-housing solution or a new place to live, without a pre-existing, direct, and legitimate connection to a specific Native American tribe and its enrollment criteria.

Recommendation (Rekomendasi Pembelian)

Given the unique nature of "Native American Housing Programs" as a "product" for co-housing enthusiasts, our recommendation must be highly nuanced:

For Enrolled Native American Tribal Members:

Highly Recommended (A Must-Consider): If you are an enrolled member of a tribe with a functioning housing authority, exploring these programs is paramount. They offer a pathway to affordable, community-centered, and culturally appropriate housing that aligns perfectly with the core values of co-housing, but within the context of your own rich heritage and sovereign nation. This is not just housing; it’s an investment in your community’s future and cultural resilience. Engage with your Tribal Housing Authority, understand their specific offerings (rental, homeownership, rehabilitation), and actively participate in the process.

For Non-Native Individuals Interested in Co-Housing:

Not Recommended as a Direct Solution or "Purchase": It is crucial to understand that Native American housing programs are not a viable or appropriate direct option for non-Native individuals seeking co-housing. Attempting to "join" these programs without tribal affiliation would be disrespectful to tribal sovereignty and the historical context they address.

However, Highly Recommended as a Model and Source of Inspiration:

While direct participation is virtually impossible, we strongly recommend that non-Native co-housing enthusiasts study and draw inspiration from the fundamental principles evident in Native American communities:

- Learn about Tribal Sovereignty: Understand the history, governance, and self-determination of Native nations. This knowledge fosters respect and helps contextualize why these housing programs exist as they do.

- Embrace Community-Centric Values: Observe how Indigenous cultures prioritize collective well-being, intergenerational support, and a deep connection to the land. Seek to integrate these authentic values into the co-housing communities you can form or join.

- Support Native Initiatives: Instead of seeking to join their specific programs, look for ways to support Native American-led housing and community development efforts through advocacy, donations to tribal non-profits, or partnerships that respect tribal self-determination.

- Seek Analogous Solutions: If the values of sustainability, intergenerational living, and strong community appeal to you, explore formal co-housing communities, eco-villages, or intentional communities in your area that are open to all and actively build these principles from the ground up.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Community and a Call for Respect

Native American housing programs, while not an accessible "product" for the general co-housing market, stand as powerful examples of community-driven, culturally resonant, and sustainable living. They embody many of the ideals that modern co-housing movements strive for: deep social connection, intergenerational support, and a profound respect for the environment.

For those within Native nations, these programs are a vital lifeline and a testament to resilience and self-determination. For those outside, they serve as a profound educational opportunity and a source of inspiration. The "purchase" recommendation for non-Natives is not to seek direct entry, but rather to invest in understanding, respecting, and learning from the enduring communal wisdom of Indigenous peoples, and to apply those lessons to the co-housing movements they can actively participate in, always with an eye towards genuine community building and cultural humility. The future of sustainable, connected living can draw immense strength from these ancient, yet perpetually relevant, models.