Navigating the Nexus: A Comprehensive Review of Sovereignty’s Impact on Tribal Land Mortgages

In the complex tapestry of American land ownership and financial systems, the unique status of tribal lands presents a fascinating and often challenging landscape, particularly concerning homeownership and economic development. This article undertakes a comprehensive "review" of the concept and practical implications of tribal sovereignty on the process of securing mortgages on Native American lands. While not a tangible product in the traditional sense, "understanding the impact of sovereignty" is a critical framework, a necessary lens through which all stakeholders must view this issue. We will examine its inherent strengths (pros), its significant hurdles (cons), and offer "purchase recommendations" – actionable strategies for fostering more equitable and accessible homeownership opportunities within tribal nations.

The "Product" Under Review: The Interplay of Sovereignty and Land Tenure

To appreciate the "product" – our understanding of this intricate relationship – we must first grasp its foundational elements. Tribal nations possess inherent governmental sovereignty, a status predating the United States, affirmed through treaties, federal statutes, and Supreme Court decisions. This sovereignty means tribal governments retain broad authority over their lands and members, acting as distinct political entities.

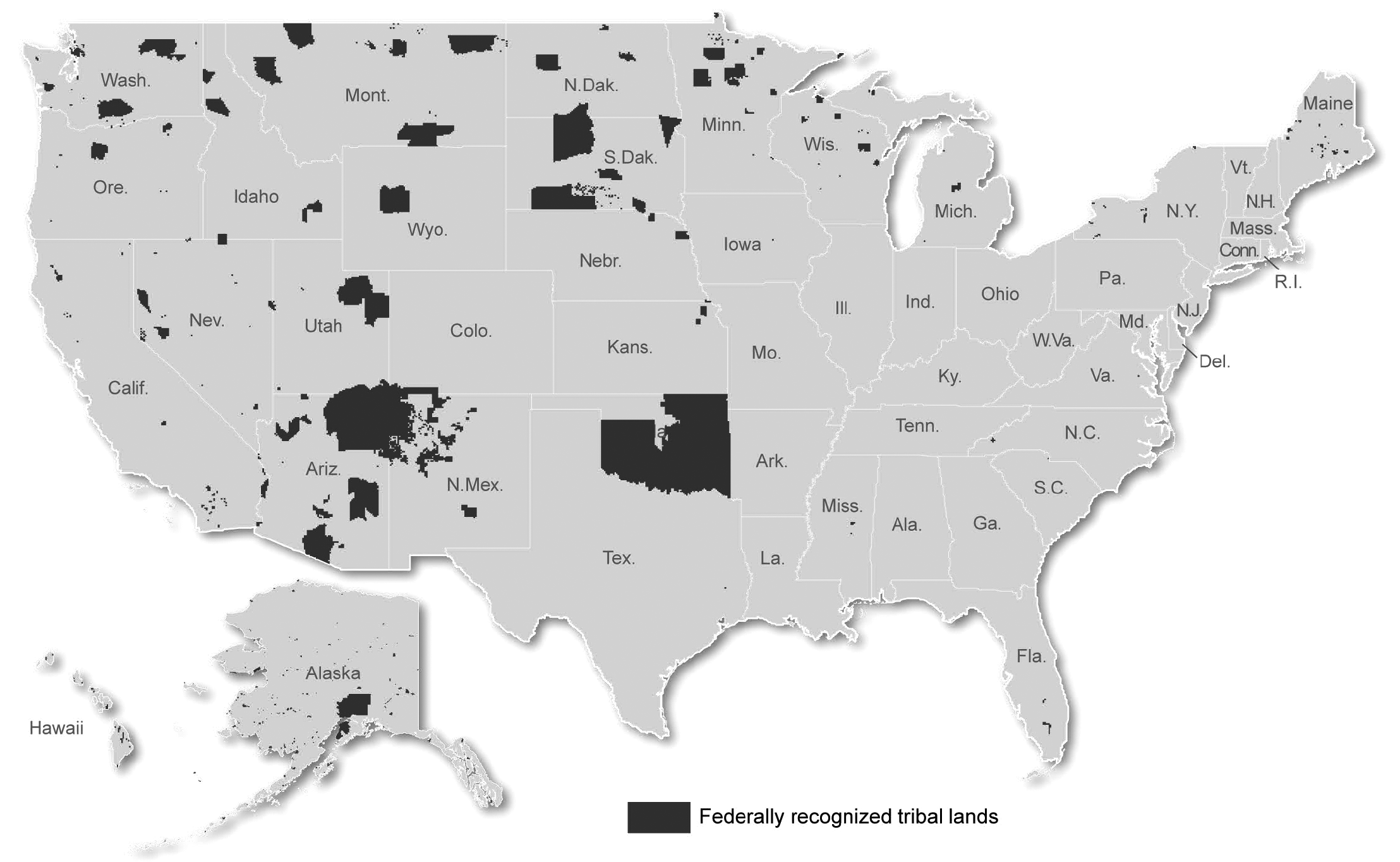

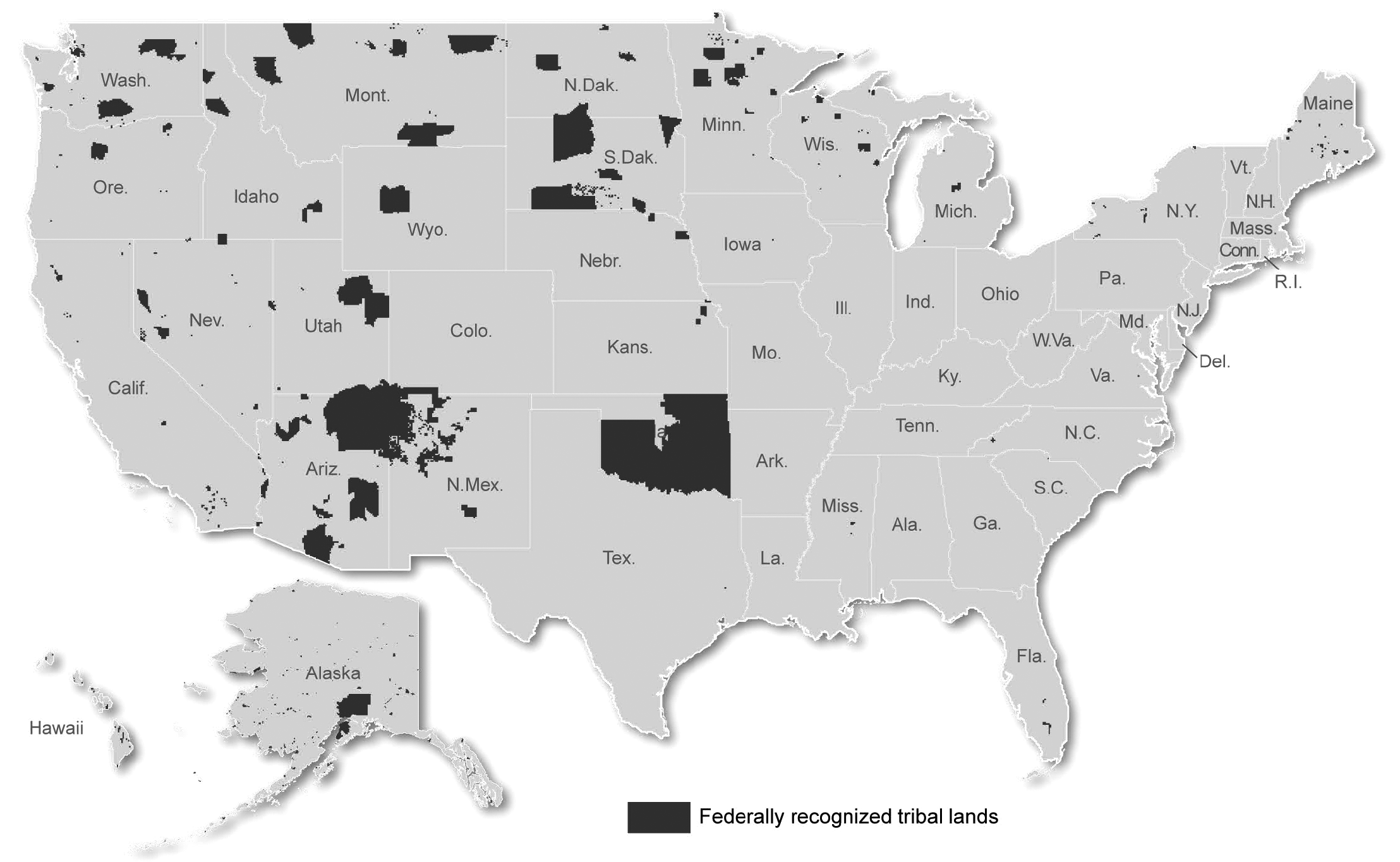

Crucially, much of Native American land is held in a unique legal status known as "trust land." This means the land is owned by the United States government in trust for the benefit of a tribe or individual tribal members. This trust status, a legacy of federal Indian policy, was originally intended to protect tribal assets but has, ironically, become a significant impediment to conventional financial transactions, including mortgages. Additionally, some tribal lands are "restricted fee" lands, owned directly by individual tribal members but still subject to federal restrictions on alienation, or "allotments," parcels of trust land assigned to individual tribal members, often with complex, fractionated ownership.

The "product" under review, therefore, is the entire ecosystem shaped by these legal and historical realities. It’s the framework of rules, precedents, and practices that dictates whether a tribal member can obtain a mortgage, whether a tribal nation can develop housing, and how external financial institutions engage with these unique jurisdictions.

"Features" and "Benefits": The Pros of Sovereignty’s Impact

While often perceived as a barrier, tribal sovereignty, when properly understood and leveraged, offers profound advantages for tribal nations and their members. These benefits underscore the potential for self-determination and culturally appropriate development.

-

Self-Determination and Tailored Governance:

- Pro: Sovereignty empowers tribal governments to create their own housing codes, land use ordinances, and legal frameworks, such as those enabled by the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA) and the Tribal Law and Order Act (TLOA). This allows tribes to develop solutions that are culturally relevant, meet specific community needs, and reflect local priorities, rather than being dictated by external, often ill-fitting, state or county regulations.

- Impact: This means housing can be designed to incorporate traditional architectural elements, communal spaces, or extended family living arrangements, fostering community cohesion and cultural preservation.

-

Protection of Tribal Lands and Resources:

- Pro: The trust status, a direct consequence of federal trust responsibility rooted in sovereignty, prevents the easy alienation of tribal lands. This protects against predatory lending practices, speculative land grabs, and ensures the long-term preservation of ancestral territories for future generations.

- Impact: While challenging for conventional lending, this protection is fundamental to tribal survival and cultural continuity. It ensures that homes built on tribal lands contribute to the permanent wealth and stability of the community, rather than being susceptible to market forces that could displace tribal members.

-

Innovation in Tribal Lending and Financial Instruments:

- Pro: Faced with mainstream financial sector reluctance, many tribal nations have established their own housing authorities, tribal lending institutions (TLIs), and innovative leasehold mortgage programs. These entities are uniquely positioned to understand the local context, build relationships of trust, and design financial products that align with tribal legal frameworks. The HEARTH Act (Helping Expedite and Advance Responsible Tribal Homeownership Act of 2012) further strengthens this by allowing tribes to develop and implement their own leasing regulations for residential, business, and other purposes, streamlining the BIA approval process for these leases.

- Impact: This fosters self-sufficiency and creates pathways to homeownership that would otherwise be unavailable, demonstrating the power of self-governance in overcoming systemic barriers.

-

Access to Specialized Federal Programs:

- Pro: Tribal sovereignty is the basis for government-to-government relationships, enabling the creation and access to federal programs specifically designed to address housing and infrastructure needs on tribal lands. The HUD Section 184 Indian Home Loan Guarantee Program is a prime example, guaranteeing mortgages for Native American borrowers on and off tribal lands, mitigating risk for lenders, and offering more flexible underwriting criteria.

- Impact: These programs are vital lifelines, bridging the gap between conventional lending and the unique challenges of tribal land tenure, making homeownership a reality for thousands of Native American families.

-

Community-Driven Economic Development:

- Pro: When homeownership becomes more accessible, it injects capital into tribal economies, creates jobs, and builds local wealth. Sovereign control over land use and development planning allows tribes to strategically integrate housing with other economic initiatives, such as commercial ventures, healthcare facilities, and educational institutions.

- Impact: This holistic approach to development ensures that housing isn’t just shelter but a cornerstone of sustainable, self-determined community growth.

"Drawbacks" and "Challenges": The Cons of the Current Landscape

Despite the inherent strengths, the current understanding and implementation of sovereignty’s impact on mortgages present significant, often systemic, challenges that hinder homeownership and economic growth on tribal lands.

-

Legal Complexity and Jurisdictional Ambiguity:

- Con: The overlay of federal, tribal, and sometimes state laws creates a labyrinthine legal environment. Determining which laws apply to a specific land parcel or transaction can be incredibly complex, especially on trust lands where federal jurisdiction is paramount, tribal jurisdiction is inherent, and state jurisdiction is often preempted or limited.

- Impact: This uncertainty deters lenders, title companies, and appraisers who are accustomed to clear, uniform legal frameworks in fee-simple land transactions.

-

Lender Reluctance and Risk Aversion:

- Con: Many mainstream financial institutions perceive lending on tribal lands as inherently risky due to the complexities of land tenure, foreclosure procedures, and the lack of familiarity with tribal legal systems. The fear of being unable to repossess collateral (the land/home) in the event of default is a primary deterrent.

- Impact: This results in a "credit desert" on many reservations, severely limiting access to conventional mortgages, higher interest rates when loans are available, and a reliance on federal guarantee programs that, while vital, are not a comprehensive solution.

-

Collateral Issues and Foreclosure Challenges:

- Con: The trust status of much tribal land means it cannot be alienated (sold) without federal approval. This fundamentally undermines the traditional mortgage model, where the land serves as collateral that can be seized and sold by a lender in foreclosure. Even on restricted fee or allotted lands, the process is often cumbersome, involving the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Tribal foreclosure procedures, where they exist, may differ significantly from state laws.

- Impact: Lenders are understandably hesitant to finance properties where their primary recourse in default is severely limited or non-existent by conventional standards. This remains the single largest impediment to private capital investment in tribal housing.

-

Title and Appraisal Difficulties:

- Con: Securing clear, insurable title on trust or allotted lands is a monumental task. Fractionalized ownership, where a single parcel of land can be owned by hundreds of descendants, makes title searches incredibly complex and often impossible to resolve. Appraisals are also difficult due to a lack of comparable sales data on tribal lands and the unique value proposition of land that cannot be freely bought and sold.

- Impact: Without clear title and reliable appraisals, mortgages cannot be underwritten, and the secondary market (Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac) is unwilling to purchase these loans, further isolating tribal land lending.

-

Capacity Gaps and Bureaucratic Hurdles:

- Con: While tribes have the sovereign right to develop their own laws, some tribal governments, particularly smaller ones, may lack the financial resources, legal expertise, or administrative capacity to develop and implement robust tribal housing codes, land registries, or streamlined leasing processes. The BIA, while having a trust responsibility, is often criticized for its slow, cumbersome, and understaffed processes for approving leases, rights-of-way, and other land transactions.

- Impact: These administrative burdens create delays, increase costs, and frustrate both tribal members and potential lenders, slowing down housing development.

-

Limited Secondary Market Participation:

- Con: Due to the aforementioned risks and complexities, there is very little secondary market activity for mortgages on tribal lands. Lenders typically sell their mortgages to entities like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to free up capital for new loans. The unique nature of tribal land mortgages makes them unattractive to these secondary market players.

- Impact: This further limits the pool of available capital for tribal housing, as lenders cannot easily offload the risk, making them less likely to originate such loans in the first place.

"User Experience": The Human Impact

The cumulative effect of these pros and cons is a dramatically different "user experience" for a tribal member seeking to own a home compared to a non-Native American. While federal programs offer some relief, the path to homeownership on tribal lands is often longer, more arduous, and fraught with uncertainty. It’s a journey that requires exceptional patience, a deep understanding of complex legal frameworks, and often, a reliance on tribal or specialized federal resources that are not universally available. This disparity perpetuates wealth gaps and hinders the ability of tribal communities to build intergenerational assets through homeownership.

"Recommendations for Purchase": Strategies for a Better Future

To truly harness the benefits of sovereignty and mitigate its current drawbacks, a multi-faceted approach involving all stakeholders is required. Our "purchase recommendations" focus on fostering collaboration, education, and innovation.

-

For Tribal Nations:

- Invest in Legal and Administrative Capacity: Develop and implement robust, clear, and comprehensive tribal housing codes, land registries, and leasehold mortgage ordinances (e.g., utilizing the HEARTH Act). Ensure these codes include clear provisions for default and dispute resolution.

- Strengthen Tribal Financial Institutions: Support and expand tribal lending institutions (TLIs) and tribal housing authorities, empowering them to offer culturally appropriate and flexible financial products.

- Educate and Partner: Proactively engage with potential lenders, providing education on tribal sovereignty, land codes, and the reliability of tribal legal systems.

-

For Federal Government (BIA, HUD, Treasury):

- Streamline BIA Processes: Significantly reform and adequately staff the BIA’s land title and trust services to expedite approvals for leases, rights-of-way, and other land transactions critical for housing development.

- Expand and Innovate Federal Programs: Fully fund and expand programs like Section 184 and NAHASDA. Explore new guarantee programs or direct lending initiatives that specifically address the unique challenges of trust land collateral.

- Promote HEARTH Act Implementation: Provide technical assistance and funding to tribes to develop their own HEARTH Act leasing codes, reducing reliance on BIA approvals.

-

For Financial Institutions (Lenders, Title Companies, Appraisers):

- Cultural Competency and Education: Invest in training for staff on tribal sovereignty, land tenure, and federal Indian law. Understand the unique legal and cultural context of tribal nations.

- Develop Specialized Products: Work with tribal governments and housing authorities to create loan products tailored to tribal land systems, potentially leveraging tribal guarantees or innovative leasehold structures.

- Embrace Section 184: Actively participate in the HUD Section 184 program, which is designed to mitigate lender risk on tribal lands.

- Collaborate on Title Solutions: Engage with tribal nations and federal agencies to explore innovative solutions for title assurance, such as tribal title registries or alternative forms of title insurance.

-

For the Secondary Market (Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac):

- Develop Tribal Land Mortgage Products: Work with HUD and tribal stakeholders to develop standardized products that can be purchased on the secondary market, addressing the unique risk profiles in a structured manner. This could involve enhanced guarantees or pooled tribal mortgages.

- Increase Understanding: Engage in educational initiatives to build internal expertise on tribal land lending.

Conclusion

Understanding the impact of sovereignty on tribal land mortgages is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical endeavor with tangible implications for the economic well-being and self-determination of Native American communities. While the inherent complexities of tribal land tenure and the legacy of federal Indian policy have created significant barriers to conventional homeownership, tribal sovereignty also provides the bedrock for innovative, culturally appropriate solutions.

The "product" – our collective understanding and the systems built upon it – is currently a mixed bag. It offers the profound benefits of self-determination and cultural preservation but comes with the heavy costs of legal complexity, lender reluctance, and systemic financial exclusion. By embracing collaboration, fostering education, streamlining bureaucratic processes, and promoting innovative financial instruments, all stakeholders can work towards a future where tribal sovereignty is not a barrier, but a powerful foundation for robust homeownership, wealth creation, and thriving tribal nations. This "purchase recommendation" is not for a simple product, but for a commitment to equity, respect, and a more just financial landscape.