Reviewing the Lifeline: An Evaluation of Native American Housing Assistance for Natural Disaster Victims

Product Name: Native American Housing Assistance for Natural Disaster Victims (NAHADN)

Category: Critical Infrastructure & Humanitarian Aid System

Providers: Federal Agencies (FEMA, HUD, BIA), Tribal Governments, Non-Profits, State Entities

Target User: Native American individuals, families, and communities residing on tribal lands or in tribally designated areas, affected by natural disasters.

Executive Summary: A System Under Strain, Yet Indispensable

The "product" under review, Native American Housing Assistance for Natural Disaster Victims (NAHADN), is not a tangible item but a complex, multi-faceted system designed to provide a lifeline to some of the nation’s most vulnerable populations. In the face of increasingly frequent and intense natural disasters – from devastating wildfires and floods to blizzards and hurricanes – the effectiveness of this assistance is a matter of life and death, cultural preservation, and sovereign resilience.

This review evaluates NAHADN based on its "features," "performance," "user experience," and overall "value proposition." While the system offers dedicated programs and a foundational commitment to tribal sovereignty, its performance is frequently hampered by bureaucratic hurdles, underfunding, jurisdictional complexities, and a persistent struggle to reconcile federal mandates with unique tribal needs and cultural contexts. The "user experience" is often fraught with delays, frustration, and a sense of being an afterthought.

Despite its significant flaws, NAHADN remains an indispensable mechanism. Its very existence acknowledges a federal trust responsibility and the disproportionate impact of disasters on Native communities. However, for NAHADN to truly meet its potential, it requires a significant overhaul, moving from a reactive, often fragmented approach to a proactive, culturally informed, and tribally-driven model.

Understanding the Landscape: The "Operating Environment"

Before delving into the specifics of NAHADN, it’s crucial to understand the unique "operating environment" in which it functions. Native American communities face distinct challenges that exacerbate disaster impacts and complicate recovery:

- Sovereignty and Trust Lands: The complex legal status of tribal lands (trust lands, fee simple, allotments) creates jurisdictional ambiguities that can delay or outright prevent federal aid.

- Geographic Isolation: Many tribal communities are remote, making access for emergency responders and delivery of aid difficult and costly.

- Pre-existing Vulnerabilities: High rates of poverty, inadequate housing, and aging infrastructure mean many communities are already living on the brink, with little capacity to absorb disaster shocks.

- Cultural Significance: Homes are not just structures; they are repositories of family history, cultural practices, and community identity. Displacement and destruction carry profound cultural and spiritual costs.

- Historical Trauma: A legacy of broken treaties and federal policies fosters deep-seated mistrust in government agencies, impacting willingness to engage with assistance programs.

These factors mean that a "one-size-fits-all" disaster response, often designed for mainstream populations, is fundamentally ill-suited for Native American communities.

Features & Functionality: What NAHADN Promises

NAHADN encompasses a range of programs and policies primarily managed by three federal departments, often in conjunction with tribal governments and non-profits:

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA):

- Individual and Households Program (IHP): Provides financial assistance and direct services to eligible individuals and families who have uninsured or under-insured necessary expenses and serious needs caused by a disaster. This includes housing assistance (rental assistance, temporary housing units, home repair, or replacement).

- Public Assistance (PA): Helps communities cover costs for debris removal, emergency protective measures, and repair/replacement of disaster-damaged public facilities (e.g., roads, bridges, utilities, tribal government buildings).

- Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD):

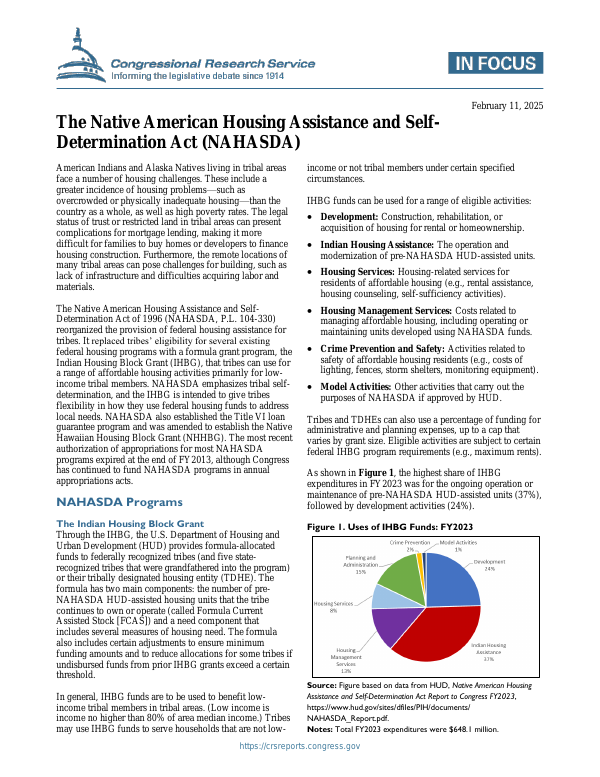

- Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA): Provides block grants to eligible Indian tribes and tribally designated housing entities (TDHEs) to address affordable housing needs. While not solely disaster-focused, NAHASDA funds can be flexibly used for housing development, rehabilitation, and emergency repairs, making it a critical component of disaster recovery.

- Community Development Block Grant – Indian Tribes and Alaska Native Villages (ICDBG): Supports housing, community facilities, and economic development activities, including disaster recovery and mitigation efforts.

- Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA):

- Emergency Management: Coordinates with tribes and other federal agencies for preparedness, response, and recovery efforts, often acting as a liaison.

- Roads and Infrastructure: Can provide support for repairing BIA-maintained roads and other infrastructure vital for recovery.

- Tribal Governments: Increasingly, tribes are building their own emergency management capacities, utilizing federal funds, and leveraging their sovereign authority to lead response and recovery efforts.

Key "Features" Highlights:

- Dedicated Funding Streams: NAHASDA and ICDBG provide specific, though often insufficient, funding for Native communities.

- Acknowledgement of Sovereignty: The framework theoretically allows tribes to determine their own housing needs and recovery strategies.

- Comprehensive Scope: Aims to cover immediate shelter, temporary housing, and long-term rebuilding.

The "User Experience": Challenges and Frustrations

The "user experience" for Native American disaster victims navigating NAHADN is frequently characterized by immense frustration and significant delays.

- Bureaucratic Maze: Applying for assistance often involves interacting with multiple federal agencies, each with its own forms, deadlines, and eligibility criteria. This complexity is daunting for anyone, let alone someone who has just lost everything.

- FEMA’s "Disaster Declaration" Bottleneck: Federal assistance is contingent on a presidential disaster declaration. Delays in declarations, or a failure to declare for smaller, localized events, leave communities without immediate aid.

- Eligibility Hurdles:

- Land Ownership: Proving homeownership on trust lands can be incredibly difficult, as deeds are often not recorded in the same way as fee simple lands. This is a major barrier for FEMA assistance.

- Income Limits: Federal programs often have income limits that, while intended to target need, can exclude some families who, while poor, might exceed arbitrary thresholds.

- Slow Response Times: The remote nature of many tribal communities, coupled with logistical challenges and federal red tape, often means aid arrives weeks or even months after a disaster, long after immediate needs have passed.

- Cultural Insensitivity: Standardized housing solutions (e.g., temporary trailers) often fail to account for multi-generational living arrangements, cultural practices, or spiritual needs, leading to feelings of alienation and further trauma.

- Infrastructure Deficiencies: Rebuilding is meaningless if there’s no reliable water, sanitation, or electricity. Many tribal communities lack basic infrastructure, and NAHADN often struggles to integrate housing recovery with broader infrastructure development.

- Language Barriers: For elders or those with limited English proficiency, navigating complex federal applications without adequate translation services is a significant hurdle.

- Data Gaps: A lack of comprehensive data on housing conditions and disaster impacts in Native communities hinders effective planning and resource allocation.

Pros: The Strengths and Advantages of NAHADN

Despite its shortcomings, NAHADN possesses critical strengths:

- Recognition of Unique Needs and Sovereignty: The existence of programs like NAHASDA and ICDBG, specifically for Native communities, signifies an acknowledgment of the federal trust responsibility and tribal sovereignty. This allows for more culturally relevant, though often underfunded, housing solutions than purely mainstream programs.

- Tribal Self-Determination: When effectively implemented, NAHASDA empowers tribal governments to design and administer their own housing programs, fostering local capacity and ensuring solutions are tailored to specific community needs and cultural values.

- Flexible Funding (NAHASDA/ICDBG): These block grants offer greater flexibility than many federal programs, allowing tribes to prioritize based on local needs, including disaster preparedness and recovery, rather than being bound by rigid federal categories.

- Emergency Response Coordination (FEMA): While often slow, FEMA’s involvement does bring significant resources and coordination capabilities that many smaller tribes would struggle to mobilize independently. Its Public Assistance program is crucial for rebuilding critical infrastructure.

- Capacity Building: Over time, engagement with NAHADN programs has led to the growth of tribal housing authorities and emergency management offices, enhancing tribal self-sufficiency and resilience.

- Mitigation Potential: Funds from various sources can be used for pre-disaster mitigation efforts, such as elevating homes in flood zones or creating defensible space against wildfires, which is critical for long-term safety.

Cons: The Disadvantages and Areas for Improvement

The "cons" of NAHADN are substantial and often overshadow its strengths, hindering its overall effectiveness:

- Insufficient and Inconsistent Funding: The primary drawback is a chronic lack of adequate funding. NAHASDA and ICDBG are consistently underfunded, meaning tribes cannot fully address pre-existing housing needs, let alone recover from major disasters. Recovery often outstrips available resources.

- Bureaucratic Complexity and Red Tape: The multi-agency approach, while well-intentioned, creates an labyrinthine system. Eligibility criteria, application processes, and reporting requirements vary widely and are often contradictory, leading to delays and administrative burdens for tribal governments.

- Jurisdictional Quandaries: The land tenure system on reservations (trust lands, allotments) often clashes with federal program requirements (e.g., FEMA’s proof of ownership), creating insurmountable barriers for individual applicants.

- Slow and Inequitable Response: Native communities frequently report being last in line for federal assistance. Delays in disaster declarations, assessments, and fund disbursement exacerbate suffering and prolong displacement.

- Cultural Insensitivity: Standard federal housing solutions often fail to respect traditional building practices, extended family structures, or spiritual connections to land and home, leading to culturally inappropriate or even harmful "solutions."

- Lack of Pre-Disaster Preparedness & Mitigation Focus: While some funds can be used for mitigation, the system remains predominantly reactive. A lack of sustained investment in pre-disaster planning and infrastructure resilience leaves communities vulnerable to recurring damage.

- Data Deficiencies: The absence of comprehensive, disaggregated data on Native American housing and disaster impacts makes it difficult to assess needs accurately, advocate for appropriate funding, or evaluate program effectiveness.

- Staffing and Expertise Gaps: Tribal governments often lack the staff and technical expertise to navigate complex federal regulations, write successful grants, or manage large-scale recovery projects, especially in smaller, remote communities.

- Limited Long-Term Solutions: While emergency and temporary housing are crucial, the system often struggles to provide sustainable, long-term housing solutions that contribute to community rebuilding and economic development.

The "Value Proposition" and "Purchase" Recommendation

The "value proposition" of NAHADN is undeniable in its intent and necessity. It attempts to fulfill a federal trust responsibility and address the acute housing needs of Native communities post-disaster. However, its "performance" metrics (speed, equity, cultural appropriateness, comprehensiveness) are consistently low.

Recommendation: "Hold" with a Strong Call for Immediate and Substantial "Upgrade" and "Reinvestment."

This is not a "product" to be discarded, but one that desperately needs a complete overhaul and significant investment to become truly effective and equitable.

Here’s a multi-faceted "upgrade" recommendation:

- Streamline and Consolidate: Create a single, coordinated federal office or a dedicated inter-agency task force specifically for Native American disaster response and recovery, with tribal liaisons. This would simplify the application process and reduce bureaucratic hurdles.

- Increase Funding and Flexibility: Significantly increase annual appropriations for NAHASDA and ICDBG, earmarking substantial portions for disaster preparedness, mitigation, and recovery. Provide greater flexibility for tribes to use these funds according to their specific needs, including land acquisition and infrastructure development.

- Amend Eligibility Requirements:

- Address Land Tenure: Revise FEMA and other federal program regulations to explicitly accommodate tribal land tenure systems, making it easier for individuals on trust lands to prove occupancy and eligibility.

- Culturally Appropriate Assessments: Develop assessment criteria that recognize multi-generational households, traditional building materials, and the cultural value of homes.

- Prioritize Pre-Disaster Mitigation: Shift focus from purely reactive response to proactive mitigation. Invest heavily in resilient infrastructure (water, sanitation, power), hazard mapping, and culturally appropriate building codes and practices on tribal lands.

- Enhance Tribal Capacity: Fund tribal emergency management offices, provide technical assistance, training, and resources for grant writing, project management, and culturally competent disaster response.

- Expedite Disaster Declarations and Response: Establish clearer, faster mechanisms for disaster declarations on tribal lands, and ensure equitable and timely deployment of resources.

- Culturally Competent Response: Mandate cultural competency training for all federal and state personnel involved in disaster response on tribal lands. Support tribal-led recovery efforts that incorporate traditional ecological knowledge and community-specific housing designs.

- Improve Data Collection: Invest in comprehensive data collection on housing conditions, disaster impacts, and recovery progress in Native communities, led in partnership with tribes, to inform policy and resource allocation.

- Direct Tribal Access to Federal Programs: Remove intermediaries where possible and allow tribes direct access to federal disaster programs, bypassing state governments if desired.

Conclusion: A Path Towards True Resilience

The current state of Native American housing assistance for natural disaster victims is a stark reflection of historical inequities and ongoing systemic challenges. While the framework exists to address critical needs, its implementation is often a testament to federal neglect and bureaucratic inefficiency.

To truly honor its trust responsibility and empower Native communities to recover and thrive, the U.S. government must move beyond incremental adjustments. It must undertake a comprehensive "upgrade" of NAHADN, rooted in genuine partnership, adequate funding, and a deep respect for tribal sovereignty and cultural integrity. Only then can this indispensable "lifeline" evolve into a robust, reliable, and equitable system that helps Native American communities not just survive disasters, but build a more resilient and self-determined future.