Okay, here is a 1200-word product review style article in English about building equity in homes on reservation land, covering its advantages, disadvantages, and recommendations.

Building Equity on Sacred Ground: A Comprehensive Review of Homeownership on Reservation Lands

For many, the American dream is synonymous with homeownership and the steady accumulation of equity – a tangible asset that can secure futures, fund education, or pass wealth to the next generation. This dream, however, takes on a unique and often complex character when envisioned on the sovereign lands of Indigenous nations. Building equity in homes on reservation land is not merely a financial transaction; it’s a journey interwoven with history, culture, law, and community. This review delves into the "product" of reservation homeownership, examining its distinct features, evaluating its benefits and drawbacks, and offering recommendations for individuals and communities navigating this vital path.

The "Product" Unpacked: Understanding Homeownership on Reservation Land

To assess the value proposition of building equity on reservation land, we must first understand its foundational components. Unlike traditional fee-simple ownership where an individual owns both the house and the land it sits on outright, homeownership on most reservation lands is characterized by a unique legal framework, primarily the "trust land" status.

Trust Land Status: The vast majority of reservation lands are held in trust by the U.S. federal government for the benefit of tribes and individual tribal members. This means the tribe or individual doesn’t own the land in fee simple; rather, they hold a beneficial interest, while the federal government retains the legal title. This status was initially intended to protect tribal lands from further alienation but has inadvertently created significant hurdles for conventional homeownership and equity building.

Leasehold Interests: Consequently, individual homeownership on trust land is typically structured through long-term residential leases. A tribal member might be assigned a parcel of land by their tribe, and then they obtain a leasehold interest (e.g., a 25-year lease with options for renewal up to 99 years) on that land. This leasehold interest allows them to build a home and reside on the land, but they do not own the underlying dirt. The home itself, a chattel or fixture, is often owned by the individual, while the land remains in trust.

The Definition of Equity: In this context, equity still refers to the portion of the home’s value that the homeowner truly owns. It’s the difference between the current market value of the home and the outstanding balance of any loans secured against it. However, the calculation and realization of this equity are significantly influenced by the trust land status and the nature of the leasehold interest.

Advantages: The Benefits of Building Equity on Sacred Ground

Despite the inherent complexities, building equity in homes on reservation land offers profound and often irreplaceable advantages, extending beyond mere financial gain to encompass cultural, social, and community well-being.

-

Cultural and Spiritual Connection: Perhaps the most significant advantage is the ability to reside on ancestral lands, maintaining a deep cultural and spiritual connection to one’s heritage. This fosters a strong sense of identity, belonging, and community, which is invaluable and often transcends monetary worth. It allows families to stay close to elders, participate in tribal ceremonies, and pass on traditions.

-

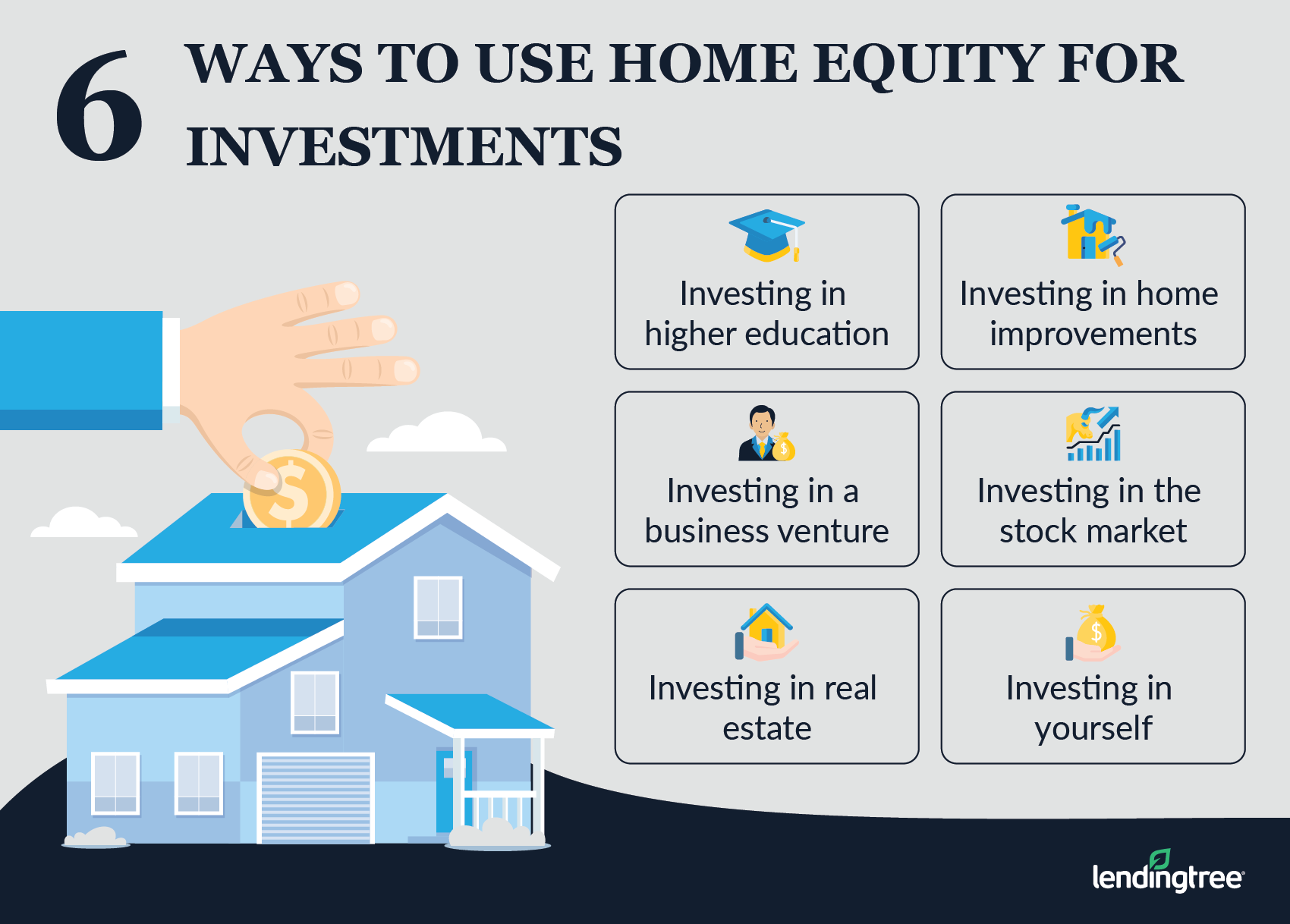

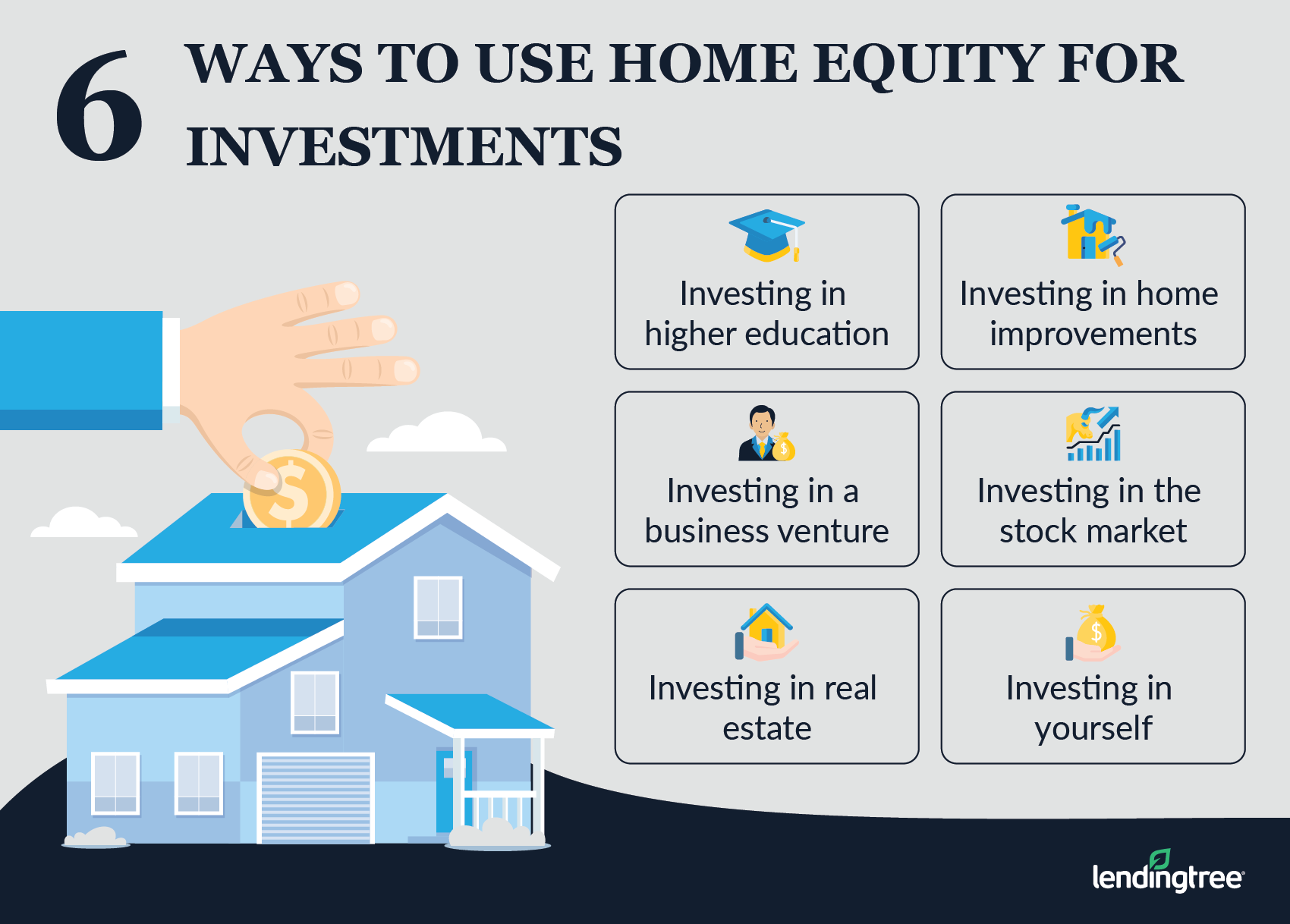

Wealth Creation and Intergenerational Transfer: For individual homeowners, accumulating equity represents a tangible asset. While the land itself cannot be alienated, the home’s value can grow, providing a financial safety net, a source of funds for education or entrepreneurship, or an asset to be passed down to children, contributing to intergenerational wealth creation within the tribal community.

-

Community Stability and Development: Homeownership fosters community stability. Homeowners are generally more invested in their neighborhoods, leading to increased civic engagement, better-maintained properties, and a more robust local economy. Each homeowner contributes to the tax base (or tribal revenue streams), supports local businesses, and creates demand for services, driving overall tribal economic development.

-

Access to Specialized Lending Programs: The unique legal landscape has prompted the creation of specialized federal loan programs designed to overcome the trust land hurdle. The Section 184 Indian Home Loan Guarantee Program (HUD) is a cornerstone, providing loan guarantees for mortgages on trust lands, making it easier for tribal members to qualify for conventional financing. Similarly, VA and FHA programs also have provisions for homes on trust lands with tribal approval.

-

Protection Against Land Alienation: The trust status, while creating lending challenges, also serves as a critical protective measure. It prevents the sale of tribal lands to non-members, safeguarding the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Indigenous nations. This ensures that homes built on these lands remain within the tribal community for future generations.

-

Tribal Self-Determination and Housing Autonomy: The growth of individual homeownership supports tribal sovereignty. Tribes can develop their own housing codes, land use policies, and financial institutions (like Native Community Development Financial Institutions – CDFIs) that reflect their values and needs, strengthening self-governance and reducing reliance on external, often culturally insensitive, housing solutions.

Disadvantages: The Hurdles on the Path to Equity

While the advantages are compelling, the path to building and realizing equity on reservation land is fraught with unique and often substantial disadvantages. These challenges primarily stem from the trust land status and historical underinvestment.

-

Complex Lending and Foreclosure Processes: This is the most significant hurdle. Because the land is held in trust, it cannot be easily collateralized or foreclosed upon by conventional lenders. This makes banks hesitant to lend, as their primary recourse in default (selling the property) is complicated by federal and tribal jurisdiction. Even with programs like Section 184, the process remains more intricate and potentially longer than off-reservation lending.

-

Appraisal Challenges: Valuing homes on reservation land is notoriously difficult. A lack of comparable sales data (due to fewer transactions and unique land tenure) and the inability to appraise the underlying land in the traditional sense often lead to lower appraisals. This can limit the amount of equity homeowners can build or borrow against, and make it harder to sell at a fair market value.

-

Infrastructure Deficits: Many reservation communities suffer from a severe lack of adequate infrastructure, including paved roads, reliable water and sewer systems, electricity, and broadband internet. This not only impacts quality of life but also significantly depresses property values and limits the appreciation potential of homes, directly hindering equity growth.

-

Limited Secondary Market: Selling a home on reservation land can be challenging. The pool of potential buyers is often limited to tribal members who qualify for the specific land lease and lending programs. This restricted market can make it difficult to realize accumulated equity quickly or at full market value, making the asset less liquid.

-

Legal and Jurisdictional Ambiguity: Navigating the interplay between federal, state, and tribal laws can be confusing. Issues related to property rights, land assignments, lease renewals, and dispute resolution can be complex, requiring specialized legal expertise and potentially leading to delays and additional costs.

-

Tribal Administrative Capacity: For tribes, managing land assignments, developing comprehensive housing codes, and administering lease agreements requires significant administrative capacity, which can be a strain on smaller or under-resourced tribal governments. Delays in these processes can directly impact a homeowner’s ability to build or access equity.

-

Leasehold Expiration and Renewal: While most residential leases on trust land are long-term (e.g., 99 years), the eventual expiration and renewal process can create uncertainty. Though renewals are common, the possibility of non-renewal, or changes in lease terms, introduces a layer of risk not present in fee-simple ownership, potentially affecting long-term equity planning.

Recommendations: Navigating the Path to Homeownership

For individuals considering building equity on reservation land, and for tribal nations aiming to facilitate this process, several key recommendations emerge.

For Individuals:

- Financial Literacy and Education: Prioritize understanding the unique aspects of reservation homeownership, including lease agreements, tribal housing policies, and specialized loan programs like Section 184. Seek out financial counseling tailored to Native American homeowners.

- Engage with Tribal Housing Authorities: Work closely with your Tribal Housing Department or Authority. They are invaluable resources for understanding land assignment processes, tribal housing codes, and available tribal or federal assistance programs.

- Explore Section 184 and Other Federal Programs: Research and utilize the Section 184 program. Understand its benefits and requirements. Also, investigate VA (Veterans Affairs) and FHA (Federal Housing Administration) loans, as they also have provisions for homes on trust lands.

- Understand Lease Agreements Thoroughly: Before signing, ensure you fully comprehend the terms of your residential lease, including its duration, renewal options, any restrictions on improvements, and responsibilities for maintenance and repairs.

- Invest in Home Maintenance and Improvements: To maximize equity growth, diligently maintain and improve your home. Document all improvements, as they directly contribute to the home’s value and can be crucial during appraisals.

- Plan for the Future: Consider the long-term implications of your homeownership. Discuss with your family how you plan to pass the home on to the next generation, factoring in tribal policies and lease agreements.

For Tribal Nations and Policymakers:

- Develop Robust Tribal Housing and Land Use Codes: Implement clear, comprehensive, and streamlined tribal housing and land use codes that address leasehold interests, home construction standards, property maintenance, and dispute resolution. Clarity reduces risk for lenders and homeowners.

- Invest in Infrastructure Development: Prioritize investment in critical infrastructure – roads, water, sewer, and broadband. These improvements are fundamental to increasing property values and enhancing the quality of life, directly contributing to equity growth.

- Support Native CDFIs and Tribal Lending Institutions: Foster and support the growth of Native Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) and tribal lending programs. These institutions are specifically designed to address the unique needs of Native communities and can offer flexible financing solutions.

- Streamline Land Assignment and Lease Approval Processes: Reduce administrative bottlenecks in land assignment and lease approval processes. Efficiency benefits both tribal members and potential lenders.

- Advocate for Federal Program Expansion and Flexibility: Continuously advocate for the expansion, increased funding, and greater flexibility of federal programs like Section 184 and NAHASDA (Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act) to better meet the diverse housing needs of tribal communities.

- Promote Financial Literacy and Homeowner Education: Implement or support programs that provide financial literacy and homeownership education to tribal members, empowering them with the knowledge to make informed decisions and manage their assets effectively.

- Explore Innovative Solutions: Consider exploring innovative land tenure models or partnerships that could further facilitate equity building while respecting tribal sovereignty and trust land status.

Conclusion: A Foundation for the Future

Building equity in homes on reservation land is a complex yet profoundly important endeavor. It is a "product" that offers immense cultural, social, and economic returns, enabling Indigenous peoples to secure their futures on their ancestral lands. While the unique legal framework of trust land status presents distinct challenges, programs like Section 184 and the growing capacity of tribal nations are steadily paving the way for more accessible and equitable homeownership.

The journey requires patience, education, and a collaborative spirit among individual homeowners, tribal governments, and federal partners. By understanding the advantages, proactively addressing the disadvantages, and implementing thoughtful recommendations, the dream of building equity on sacred ground can not only be realized but can also become a powerful foundation for self-determination, intergenerational wealth, and thriving Indigenous communities. The value is not just in the walls and roof, but in the enduring connection to land, culture, and community that it represents.