Beyond the Blueprint: A Critical Review of BIA Housing Programs and the Quest for Indigenous Homeownership

The dream of a safe, stable, and culturally appropriate home is universal. Yet, for countless Native American families living on tribal lands, this dream remains tragically out of reach. The housing crisis in Indian Country is profound, characterized by severe overcrowding, dilapidated structures, lack of basic infrastructure, and persistent barriers to homeownership. At the heart of the federal government’s historical and ongoing response to this crisis lies the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), an agency with a complex and often fraught history.

This article aims to provide a comprehensive "product review" of the BIA’s housing programs. While not a conventional product one "buys," these programs represent a vital, albeit often insufficient, federal investment in the well-being and self-determination of Native communities. We will dissect their strengths and weaknesses, evaluate their effectiveness, and ultimately offer recommendations for their future development and the broader pursuit of housing equity in Indian Country.

Historical Context: A Foundation Built on Shifting Sands

To understand the BIA’s housing programs today, one must acknowledge their historical trajectory. For much of its existence, the BIA operated as a paternalistic overseer, directly managing many aspects of tribal life, including housing. Early BIA efforts were often characterized by cookie-cutter designs, lack of cultural sensitivity, and an emphasis on assimilation rather than empowerment. Policies like allotment (dividing communal lands into individual parcels) and forced relocation further disrupted traditional housing patterns and created lasting land tenure complexities that continue to impede housing development.

The landscape began to shift with the rise of tribal self-determination movements in the latter half of the 20th century. Legislation like the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA) of 1975 allowed tribes to assume control over federal programs, including some BIA housing initiatives. Critically, the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA) of 1996 revolutionized federal housing assistance by consolidating various programs into block grants directly to tribes (administered by HUD, not BIA), allowing for greater tribal control and culturally relevant solutions.

In this evolving context, the BIA’s direct role in constructing housing has significantly diminished. Its current housing-related functions are primarily foundational and supportive, focusing on infrastructure development, land management, loan guarantees, and technical assistance—elements crucial for any housing development to occur on tribal lands.

"Product Features": The Core Offerings of BIA Housing Programs

The BIA’s housing programs, broadly speaking, provide the underlying infrastructure and support mechanisms essential for tribal housing development. Key "features" include:

- Infrastructure Development: This is arguably the BIA’s most direct and critical contribution. Many tribal lands lack basic infrastructure – roads, water, sewer, and electricity – making any housing development impossible without these foundational elements. The BIA provides funding and technical assistance for these critical projects, often serving as the primary source of infrastructure development in remote areas.

- Land Management and Trust Responsibilities: A significant portion of tribal land is held in trust by the federal government, primarily through the BIA. This responsibility involves managing land leases, ensuring clear titles, and facilitating the complex process of fractionalized heirship land consolidation. These functions are vital for securing the land base necessary for housing construction and for enabling access to financing.

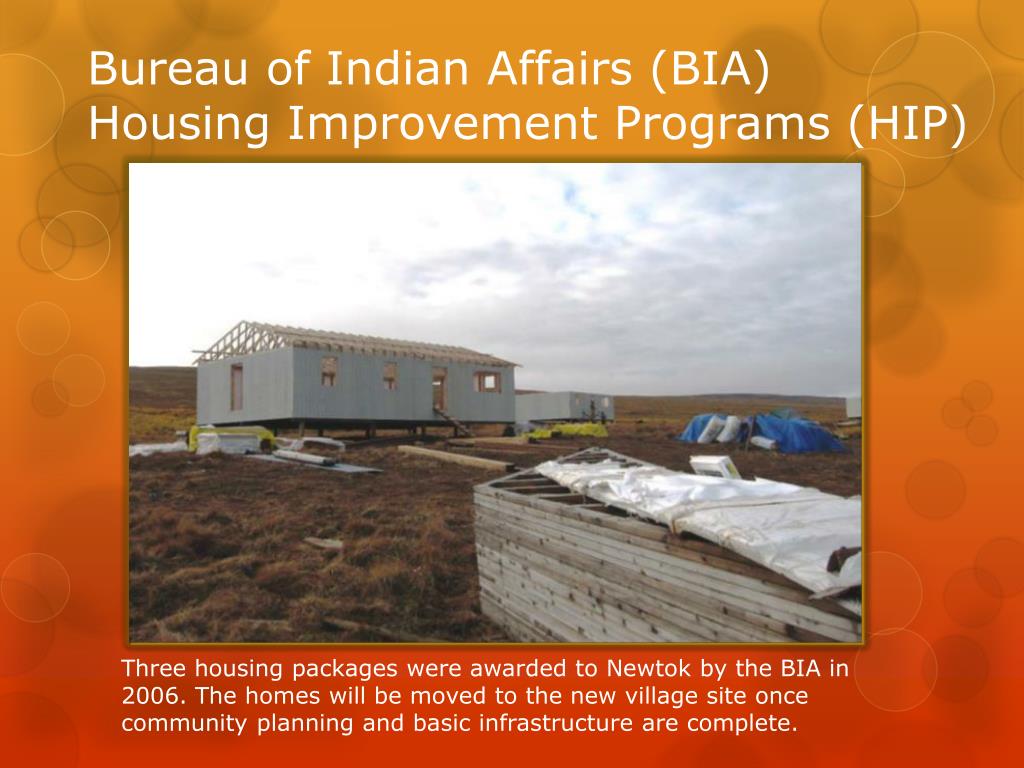

- Housing Improvement Program (HIP): One of the few direct housing assistance programs still under BIA administration, HIP provides grants for repair, renovation, and replacement of substandard housing for eligible low-income Native Americans. It serves as a program of last resort for those with no other housing options.

- Loan Guarantees: The BIA can offer guarantees for home loans, making it easier for Native Americans to obtain mortgages for homes on trust lands, where conventional lenders are often hesitant due to unique land tenure issues.

- Technical Assistance: BIA staff can provide technical guidance to tribes and individuals on various aspects of housing development, from planning and design to navigating federal regulations.

Pros: The Strengths of the System

Despite its limitations, the BIA’s involvement in housing provides several critical advantages:

- Essential Foundational Support: In many remote or underserved areas, the BIA is the only entity providing the fundamental infrastructure (roads, water, sewer, electricity) necessary for any housing to be built. Without these basic utilities, even well-funded tribal housing authorities or private developers would be unable to proceed. This foundational work directly enables subsequent housing projects, whether funded by NAHASDA or other sources.

- Addressing Trust Land Complexities: The BIA’s role as trustee for tribal lands is indispensable. Its efforts to clarify land titles, manage leases, and address fractionalized ownership are crucial for unlocking the potential for housing development. Without the BIA’s trust responsibilities, the legal and administrative hurdles for building on tribal lands would be even more insurmountable, effectively blocking access to conventional financing.

- Safety Net for the Most Vulnerable (HIP): The Housing Improvement Program (HIP), though small and perpetually underfunded, serves a vital role for the lowest-income Native Americans. It provides a lifeline for individuals and families living in severely substandard conditions, offering repairs or replacements where no other assistance is available. It directly addresses dire circumstances that could otherwise lead to homelessness or extreme health hazards.

- Facilitating Access to Financing: BIA loan guarantees are a powerful tool for overcoming the unique challenges of securing mortgages on trust lands. By mitigating risk for lenders, these guarantees make homeownership a tangible possibility for Native individuals who might otherwise be excluded from the conventional housing market. This directly contributes to wealth building and economic stability for Native families.

- Historical and Legal Mandate: The BIA’s involvement stems from the federal government’s trust responsibility to Native American tribes. Its continued presence, even in a supportive role, acknowledges this solemn obligation and provides a framework for federal engagement that, when properly resourced, can advance tribal self-determination and well-being.

- Potential for Cultural Relevance: When BIA programs effectively support tribal-led initiatives (e.g., through infrastructure for tribal housing authorities), there’s a greater potential for housing designs and community planning to reflect specific tribal cultures, traditions, and environmental contexts, fostering a stronger sense of identity and belonging.

Cons: The Challenges and Flaws

Despite these strengths, the BIA’s housing programs are plagued by significant, systemic weaknesses that severely limit their effectiveness:

- Chronic Underfunding: This is the most pervasive and debilitating flaw. BIA housing-related programs, particularly for infrastructure and HIP, are consistently and drastically underfunded relative to the immense need. This means long waiting lists, projects delayed or never started, and an inability to keep pace with population growth or address the massive backlog of existing substandard housing. The scale of the housing crisis in Indian Country simply overwhelms the resources currently allocated through the BIA.

- Bureaucracy and Red Tape: The BIA is notoriously slow and cumbersome. The complex administrative processes, layers of approvals, and intricate regulatory requirements often create significant delays for tribal projects. This bureaucratic inertia can stifle innovation, frustrate tribal housing authorities, and ultimately hinder the timely delivery of much-needed homes and infrastructure.

- Legacy of Paternalism and Mistrust: Despite efforts towards self-determination, the BIA’s historical role as a controlling entity still casts a long shadow. This can lead to a lack of trust between tribes and the agency, hindering effective collaboration. The perception, and sometimes reality, of federal control over tribal land and resources remains a sensitive issue that impacts housing initiatives.

- Limited Scope and Direct Impact: While BIA’s foundational support is crucial, its direct impact on constructing housing units is limited. The bulk of direct housing construction and rehabilitation funding for tribes now comes through HUD’s NAHASDA. This means the BIA is often a bottleneck for the initial steps (land, infrastructure), but not the primary driver of the actual housing build, leading to potential disconnects and coordination challenges between agencies.

- Inadequate Infrastructure Investment: Even with BIA’s focus on infrastructure, the existing gaps are staggering. Many tribal communities still lack reliable access to clean water, wastewater treatment, and electricity. The BIA’s funding for these critical projects is insufficient to meet the demand, leaving many areas uninhabitable or prone to health crises.

- Maintenance Backlog: Existing BIA-funded or BIA-managed housing units often suffer from a severe lack of maintenance funding. Over time, these homes fall into disrepair, becoming substandard and contributing to the overall housing crisis, rather than alleviating it. This highlights a failure to invest in the long-term sustainability of housing assets.

- Jurisdictional Complexities: The intricate legal framework surrounding trust lands, coupled with overlapping federal, state, and tribal jurisdictions, creates a minefield for housing development. Navigating these complexities, even with BIA assistance, can be incredibly time-consuming and expensive, deterring both tribal and private investment.

- Staffing and Capacity Issues: Like many federal agencies, the BIA often faces challenges with adequate staffing, high turnover, and a lack of specialized expertise in areas like housing development, infrastructure planning, and financial management, particularly at the regional and agency levels. This limits its ability to effectively support tribal initiatives.

"Purchase Recommendation": Investing in a Stronger Foundation for Indigenous Housing

Given the profound need and the complex nature of the BIA’s role, a simple "buy" or "don’t buy" recommendation is insufficient. Instead, we offer a recommendation for strategic investment, comprehensive reform, and enhanced partnership to transform BIA housing programs into truly effective instruments of tribal self-determination and well-being.

Our Recommendation: A Resounding "Invest and Reform"

The BIA’s housing programs are not a luxury; they are a fundamental necessity, serving as the essential bedrock upon which all other housing efforts in Indian Country must build. To truly address the housing crisis, the following actions are imperative:

- Massive and Sustained Increase in Funding: This is the single most critical recommendation. Congress must significantly increase appropriations for BIA infrastructure programs (roads, water, sewer, electricity) and the Housing Improvement Program (HIP). Funding should be consistent, predictable, and indexed to inflation and actual need, rather than subject to annual political whims. This investment should be seen not as an expense, but as a critical investment in public health, economic development, and human dignity.

- Streamline Bureaucracy and Empower Tribal Control: The BIA must drastically simplify its administrative processes and empower tribes with greater direct control over funding and project implementation. This means reducing layers of approval, consolidating reporting requirements, and fostering a true government-to-government relationship built on trust and efficiency. The BIA’s role should be that of a facilitator and technical resource, not a gatekeeper.

- Prioritize Infrastructure Development: A dedicated, multi-year strategic plan for infrastructure development across Indian Country, with robust BIA involvement, is essential. This plan should be developed in close consultation with tribes and prioritize projects that unlock the greatest potential for housing and economic development.

- Expand Technical Assistance and Capacity Building: The BIA should significantly enhance its capacity to provide technical assistance to tribes in areas such as grant writing, project management, housing design, construction oversight, and navigating complex land tenure issues. This will build tribal self-sufficiency and reduce reliance on external consultants.

- Reform Trust Land Administration: The BIA must continue to modernize and streamline its trust land administration. This includes accelerating efforts to consolidate fractionalized lands, simplifying leasing and permitting processes for housing development, and clarifying the legal framework to make it easier for tribes and individuals to leverage their land for economic and housing purposes.

- Foster Inter-Agency Collaboration: The BIA must work seamlessly with other federal agencies, particularly HUD (NAHASDA), USDA Rural Development, and EPA, to create a coordinated and comprehensive federal approach to Indian Country housing. Joint planning, shared resources, and synchronized funding cycles can maximize impact and reduce duplication.

- Promote Culturally Appropriate Design and Materials: The BIA should actively support tribal efforts to incorporate traditional knowledge, sustainable practices, and culturally relevant designs into housing and community planning, ensuring that homes are not just structures but extensions of Indigenous identity and values.

- Invest in Long-Term Maintenance and Sustainability: Any new housing or infrastructure built with BIA support must be accompanied by adequate, long-term funding for maintenance and operation. A focus on sustainable building practices and resilient infrastructure will ensure that investments last for generations.

Conclusion: A Path Forward for Housing Equity

The Bureau of Indian Affairs’ housing programs operate in a complex and historically charged environment. While they provide indispensable foundational support—particularly in infrastructure and land management—they are severely hampered by chronic underfunding, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and the lingering legacy of paternalism.

To achieve housing equity in Indian Country, a fundamental shift is required. The BIA must evolve from its historical role as an administrator to a true partner and enabler, providing robust, flexible, and culturally sensitive support. This demands a massive and sustained investment from the federal government, coupled with a genuine commitment to streamlining processes and empowering tribal self-determination.

The homes we live in are more than just shelters; they are the foundations of health, education, economic opportunity, and cultural preservation. By critically investing in and reforming BIA housing programs, the United States can begin to honor its trust responsibility and help Native American communities build the safe, stable, and thriving futures they deserve. The blueprint for progress exists; it now requires the political will and resources to bring it to life.