Navigating the Homeland Clause: A Comprehensive Review of Residency Requirements in Native American Housing Programs

Introduction: Unboxing a Complex Policy

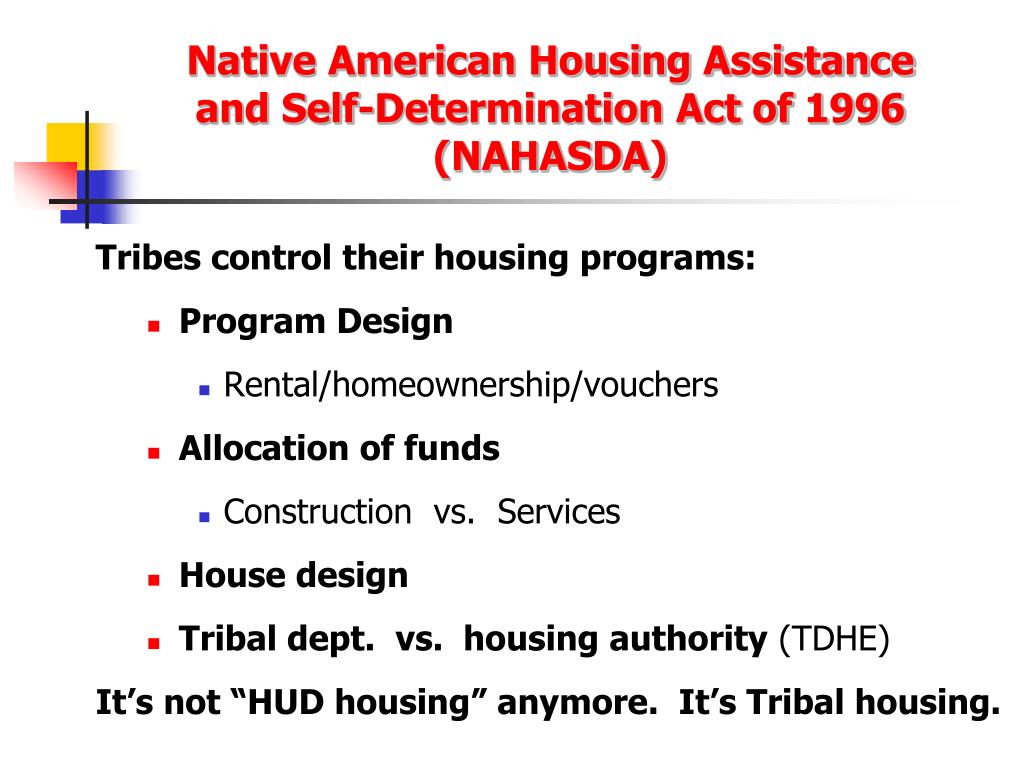

In the intricate landscape of Native American self-governance and resource allocation, housing programs stand as a critical pillar for community development, cultural preservation, and the alleviation of persistent socio-economic disparities. These programs, often funded through federal initiatives like the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA) and administered by Tribal Housing Authorities, aim to provide safe, affordable, and culturally appropriate housing solutions. However, a crucial "feature" embedded within these programs – residency requirements – presents a multifaceted challenge, eliciting both staunch support and significant critique.

This article will function as a comprehensive "product review" of these residency requirements. We will unpack their design, examine their "performance" through a lens of advantages and disadvantages, and ultimately provide a nuanced "purchase recommendation" regarding their future implementation. Understanding these requirements is not merely an administrative exercise; it’s a deep dive into tribal sovereignty, identity, resource management, and the ongoing struggle to define "community" in the face of historical trauma and modern realities.

The "Product" Specifications: Defining Residency Requirements

At its core, a residency requirement in the context of Native American housing dictates who is eligible to apply for, receive, or reside in housing units or assistance provided by a tribal government or its designated housing entity. These requirements are not uniform; they vary significantly from one tribe to another, reflecting unique cultural values, land bases, population dynamics, and political histories.

Common "specifications" or types of residency requirements include:

- Tribal Enrollment: The most fundamental requirement, often mandating that applicants be enrolled members of the specific tribe providing the housing. This is a direct assertion of tribal sovereignty and self-determination.

- Blood Quantum: Some tribes incorporate blood quantum standards, requiring a certain percentage of Native American ancestry (often from that specific tribe) for enrollment, which then dictates housing eligibility. This is a controversial legacy of colonial definitions of identity.

- Physical Presence: Requiring applicants to physically reside within the tribal jurisdiction, on the reservation, or within a designated "service area" for a specified period (e.g., 6 months, 1 year, 5 years) prior to application.

- Familial Ties: Eligibility might extend to direct descendants of enrolled members, even if not fully enrolled themselves, or to spouses of enrolled members, sometimes with caveats (e.g., must be living with the enrolled member).

- Demonstrated Need & Connection: Beyond formal enrollment, some programs prioritize applicants who can demonstrate a genuine connection to the community, an intent to return permanently, or a specific housing need that aligns with the program’s objectives.

These requirements are deeply rooted in the principles of tribal sovereignty, allowing tribes to define their own membership and control the distribution of resources intended for their people. NAHASDA, while providing federal funding, explicitly grants tribes the authority to establish their own eligibility criteria, reflecting a commitment to self-determination over paternalistic federal mandates.

Performance Review: Advantages of Residency Requirements

From a tribal perspective, the "features" of residency requirements offer substantial benefits, acting as essential tools for self-governance and community building.

1. Protection of Limited Resources:

"Resource Prioritization Feature"

Native American housing programs operate with finite resources, often struggling to meet the immense demand for safe and affordable housing on reservations. Residency requirements ensure that these scarce resources are directed towards the intended beneficiaries: enrolled tribal members and their immediate families who live within the tribal community. This prevents the dilution of assistance to individuals with weaker ties or those who may only seek to exploit program benefits without contributing to the community’s long-term well-being. It’s akin to a private club ensuring its benefits go to its dues-paying members.

2. Assertion of Tribal Sovereignty and Self-Determination:

"Sovereignty Enforcement Module"

The ability to define who belongs to the tribe and who benefits from its services is a fundamental expression of inherent tribal sovereignty. Residency requirements are a direct exercise of this right, allowing tribes to manage their affairs free from external interference. They empower tribes to make decisions that align with their specific cultural values, historical context, and immediate needs, rather than adhering to a one-size-fits-all federal mandate. This is a crucial counter-narrative to centuries of imposed policies.

3. Cultural Preservation and Community Cohesion:

"Cultural Anchor System"

By prioritizing those who live on or near the reservation, these requirements help to maintain and strengthen cultural identity, language, and traditional practices. Housing is not just shelter; it’s a foundation for community. When housing is provided to those deeply embedded in the tribal culture, it fosters a stronger sense of shared identity, encourages the intergenerational transfer of knowledge, and reinforces the social fabric of the community. It helps prevent the "brain drain" of talent and culture away from the reservation.

4. Preventing Exploitation and Gentrification:

"Community Protection Shield"

In some instances, unrestricted access to tribal housing programs could inadvertently lead to a form of internal "gentrification" or exploitation, where individuals with weaker ties or non-Native individuals might seek to benefit from affordable housing intended for the core community, potentially driving up demand or altering the community’s character. Residency requirements act as a safeguard against such scenarios, ensuring the land and resources remain primarily for the tribal members who have historical and contemporary claims to it.

5. Addressing On-Reservation Needs:

"Targeted Impact Mechanism"

The most severe housing crises often exist on reservations, characterized by overcrowding, substandard conditions, and lack of infrastructure. By focusing resources on those living within the tribal service area, programs can directly address these urgent needs, improving living standards and health outcomes for the most vulnerable populations within the tribal homeland.

Performance Review: Disadvantages and "Bugs"

While the advantages are significant, the "user experience" of residency requirements is not without its challenges and "bugs," leading to complex and often painful outcomes for many Native individuals.

1. Exclusion of Urban Natives and the Diaspora:

"Disconnection Glitch"

A significant portion of the Native American population lives in urban areas, often due to historical relocation policies, educational opportunities, or economic necessity. Strict on-reservation residency requirements can effectively exclude these individuals, even if they maintain strong cultural ties, identify deeply with their tribal heritage, and wish to return. This creates a sense of disenfranchisement, where individuals feel their identity is questioned simply because of their geographical location. They are often "too Native" for mainstream programs but "not resident enough" for tribal ones.

2. The Legacy and Divisiveness of Blood Quantum:

"Identity Crisis Feature"

Where blood quantum is a factor in enrollment (and thus housing eligibility), it introduces a deeply problematic and historically colonial construct. Blood quantum was initially imposed by the U.S. government to define who was "Indian enough" to receive treaty benefits and, ironically, to eventually "breed out" Native populations. Its continued use can create internal divisions, disenfranchise descendants with lesser blood quantum, and undermine a more holistic, culturally defined sense of belonging. It can force individuals to prove their "Nativeness" based on arbitrary biological fractions rather than cultural connection or community participation.

3. Challenges for Returning Members:

"Reintegration Barrier"

For tribal members who leave the reservation for education, military service, or employment, the requirement of prior residency upon their return can be a significant barrier. They may struggle to find temporary housing or meet the immediate residency criteria, creating a Catch-22 situation where they cannot return to the community without housing, but cannot get housing without already being in the community. This hinders the ability of tribes to attract educated and skilled members back to their homelands.

4. Impact on Mixed-Heritage Families and Spouses:

"Familial Strain Module"

When an enrolled tribal member is married to a non-Native spouse or has children who do not meet tribal enrollment or blood quantum requirements, strict residency rules can complicate housing for the entire family. It can force difficult choices, create instability, and inadvertently penalize intermarriage, even if the non-Native spouse is a deeply integrated and contributing member of the community.

5. Administrative Burden and Arbitrariness:

"Bureaucracy Overload"

Administering complex residency requirements can be resource-intensive for Tribal Housing Authorities. Verifying residency, familial ties, or blood quantum can lead to bureaucratic delays and inconsistencies. Furthermore, the application of these rules can sometimes feel arbitrary, leading to frustration and perceptions of unfairness among applicants.

6. Perpetuating Internal Divisions:

"Community Fragmentation Risk"

While intended to foster cohesion, overly strict or narrowly defined residency requirements can inadvertently create divisions within the broader Native American population. It can pit "on-reservation" against "off-reservation" Natives, or "full-bloods" against "mixed-bloods," undermining the collective strength and shared identity of Indigenous peoples.

Real-World Impact and User Experience

The human stories behind these policies are compelling. Consider the urban Native professional, educated and skilled, yearning to bring their talents back to their ancestral lands but facing a multi-year waitlist for housing, only accessible after establishing residency they cannot afford. Or the elder who moved off-reservation to be closer to specialized medical care, only to find themselves ineligible for tribal housing upon wishing to return to their community for their final years. Conversely, consider the tribal member who feels immense relief and security knowing that limited housing funds are explicitly ring-fenced for their immediate community, protecting it from external pressures.

These scenarios highlight the inherent tension between the legitimate goals of tribal self-determination and resource protection, and the often unintended consequences for individuals navigating complex identities and life circumstances shaped by centuries of colonial disruption.

"Purchase Recommendation": A Nuanced Approach

Residency requirements in Native American housing programs are not a product that can be simply "bought" or "rejected." They are a fundamental aspect of tribal sovereignty and a reflection of the unique historical, cultural, and political context of Indigenous nations. Therefore, our "recommendation" is not to abolish them, but to advocate for a flexible, holistic, and continuously evaluated approach to their design and implementation.

Our Recommendation (Policy Enhancement Package):

-

Prioritize Local Control with Flexible Frameworks:

- Recommendation: Continue to uphold tribal sovereignty in defining eligibility. However, encourage tribes to develop more flexible frameworks that reflect the diverse realities of their people.

- Implementation: NAHASDA should continue to provide block grants, empowering tribes to tailor requirements. Federal agencies should offer technical assistance in developing nuanced policies, not dictate them.

-

Broaden Definitions of "Community" and "Connection":

- Recommendation: Move beyond strict physical residency and blood quantum as sole determinants. Incorporate broader definitions that acknowledge cultural connection, participation in tribal affairs (even remotely), and a demonstrated intent to contribute to the community.

- Implementation: Tribes could consider a points-based system that credits factors like cultural language fluency, volunteer work, historical ties, or active participation in urban Native organizations affiliated with the tribe.

-

Address the Urban Native Population:

- Recommendation: Acknowledge the significant urban Native population and their housing needs.

- Implementation: Explore partnerships between tribal housing authorities and urban Indian centers to facilitate housing pathways for those wishing to return. Consider pilot programs that offer temporary or transitional housing options for returning members to establish residency. Federal funding could support "repatriation" housing initiatives.

-

Phase Out Blood Quantum as a Primary Determinant:

- Recommendation: Encourage tribes to critically re-evaluate and, where possible, phase out blood quantum as a primary criterion for housing eligibility (and ideally, for enrollment).

- Implementation: Shift towards cultural and lineal descent-based enrollment criteria that are less arbitrary and more aligned with Indigenous concepts of nationhood and belonging. This is a sensitive internal tribal decision, requiring dialogue and consensus-building.

-

Develop Pathways for Returning Professionals and Youth:

- Recommendation: Create specific programs or expedited processes for tribal members returning after higher education, military service, or skilled employment, recognizing their potential contributions.

- Implementation: Offer "returner’s grants" or specialized housing units designed to help individuals re-establish themselves within the community, fostering economic development and leadership.

-

Emphasize Transparency and Communication:

- Recommendation: Ensure housing policies are clearly communicated, easily accessible, and reviewed regularly, with opportunities for tribal member input.

- Implementation: Hold community forums, create clear online resources, and establish an appeals process for applicants.

Conclusion: An Evolving Blueprint for Home

Residency requirements for Native American housing programs are a critical, albeit often contentious, "feature" of tribal self-governance. They are a product born of necessity – to protect resources, assert sovereignty, and preserve culture in the face of ongoing challenges. However, like any product, they require ongoing evaluation and refinement to ensure they serve the broadest interests of the Native American people, both on and off the reservation.

The ideal "version" of these requirements is one that respects the inherent right of tribes to define their membership and manage their lands, while simultaneously embracing a holistic, inclusive vision of Indigenous identity that acknowledges the diaspora and the complex realities of modern Native life. It’s about finding the delicate balance between protecting the homeland and welcoming all its children home. This is not a static blueprint but an evolving framework, continually shaped by the wisdom of tribal elders, the aspirations of the youth, and the enduring spirit of self-determination.