The Foundation of Home: A Comprehensive Review of Income Requirements for Tribal Housing Assistance

Introduction: The Unseen Architecture of Opportunity

Housing is more than just shelter; it is the cornerstone of community, health, education, and economic stability. For Indigenous communities across the United States, the provision of safe, affordable, and culturally appropriate housing is not merely a policy goal but a matter of sovereignty, self-determination, and the preservation of ancestral ways of life. Historically, federal policies have often exacerbated housing disparities in tribal lands, leaving a legacy of substandard conditions, overcrowding, and chronic homelessness. In response, a complex ecosystem of federal and tribal housing programs has emerged, each with its own set of rules, regulations, and – critically – income requirements.

This article undertakes a comprehensive "product review" of these income requirements for tribal housing assistance. While not a tangible product, the system of income thresholds, eligibility criteria, and verification processes functions as a critical mechanism – a gatekeeper, if you will – determining who accesses vital housing resources. We will examine the design, performance, and user experience of this "product," highlighting its strengths ("Pros"), identifying its limitations and design flaws ("Cons"), and offering "purchasing recommendations" in the form of policy adjustments and strategic improvements to ensure a more effective and equitable system for tribal nations.

Understanding the "Product": The Mechanism of Eligibility

At its core, the "product" we are reviewing – income requirements – is designed to ensure that limited housing assistance funds are directed towards those most in need. These requirements are primarily derived from federal guidelines, notably those established by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), but often adapted and administered by tribal housing authorities (THAs) or other tribal entities.

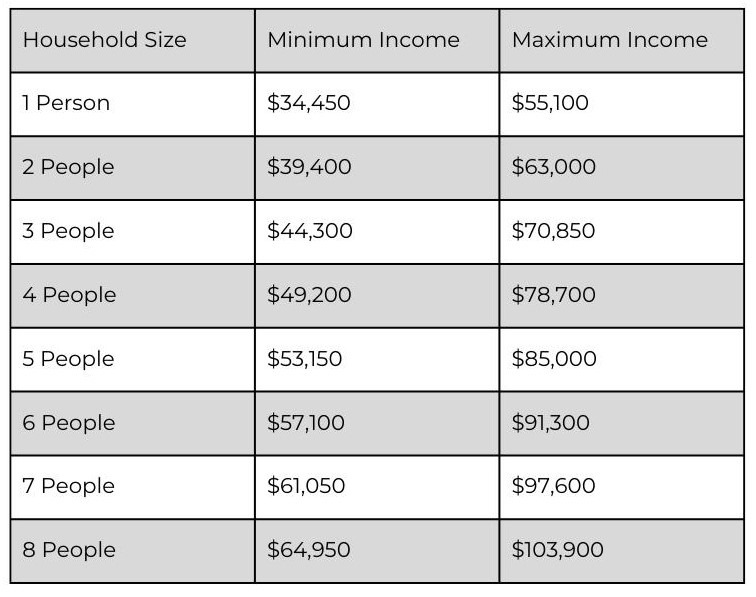

The primary federal program governing tribal housing is the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA) of 1996. NAHASDA replaced several disparate HUD programs with a block grant system, empowering tribes with greater control over their housing strategies. Under NAHASDA, tribes receive Indian Housing Block Grants (IHBG) and determine their own income limits, though they must generally serve "low-income" and "very low-income" families. HUD defines "low-income" as families with incomes not exceeding 80% of the Area Median Income (AMI) for the county or metropolitan statistical area, adjusted for family size. "Very low-income" is typically defined as 50% of AMI, and "extremely low-income" as 30% of AMI.

Beyond NAHASDA, other federal programs also contribute to tribal housing, each with specific income stipulations:

- Indian Community Development Block Grant (ICDBG): Similar to NAHASDA, focuses on low-to-moderate income beneficiaries.

- USDA Rural Development (e.g., Section 502 Direct Loans, Section 504 Home Repair): Targets very low- and low-income individuals and families in rural areas, with specific income caps that vary by location.

- HUD-VASH (Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing): Provides rental assistance to homeless veterans and their families, often aligning with Section 8 income limits.

- Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC): While not exclusively tribal, LIHTC projects on tribal lands must meet specific income targeting for tenants, usually 50% or 60% of AMI.

The "product’s" functionality involves:

- Defining Income: What constitutes "income" (wages, benefits, assets, etc.) and what deductions are allowed.

- Establishing Thresholds: Setting the specific percentage of AMI or fixed dollar amounts that determine eligibility.

- Verification: The process of documenting and confirming an applicant’s income and assets.

- Recertification: Periodic review of income to ensure continued eligibility, especially for ongoing rental assistance.

The "design philosophy" behind these requirements is multifaceted:

- Targeting Need: To ensure that assistance reaches those experiencing the most severe housing insecurity.

- Fiscal Prudence: To manage limited federal funds responsibly and achieve maximum impact.

- Preventing Abuse: To minimize fraud and ensure accountability.

- Promoting Self-Sufficiency: In some interpretations, to provide a safety net while encouraging upward mobility.

Pros: The Strengths and Advantages of the Current System

Despite its complexities, the existing framework of income requirements offers several significant advantages, acting as essential "features" that contribute to its overall utility:

-

Targeted Allocation of Resources:

- Focus on the Most Vulnerable: By setting clear income thresholds, the system ensures that the most financially vulnerable tribal members – those living below 30%, 50%, or 80% of AMI – are prioritized for assistance. This is crucial in communities where housing needs are acute and resources are scarce.

- Maximizing Impact: Directing aid to those who cannot afford market-rate housing means that every dollar spent has a greater impact on alleviating poverty and improving living conditions.

-

Fiscal Responsibility and Accountability:

- Stewardship of Public Funds: As federally funded programs, strict income requirements ensure that taxpayer money is used judiciously and for its intended purpose. This helps maintain public trust and congressional support for tribal housing initiatives.

- Preventing Misuse: Clear rules help prevent individuals who do not genuinely need assistance from monopolizing resources, thereby safeguarding the integrity of the programs.

- Data-Driven Decisions: Income data collected through the eligibility process provides valuable information for needs assessments, program planning, and advocating for future funding, demonstrating the measurable impact of housing investments.

-

Standardization and Fairness (within limits):

- Objective Criteria: While tribal contexts vary, federal income limits provide a relatively objective, albeit imperfect, benchmark for eligibility. This can reduce favoritism and ensure a more standardized approach to who receives aid.

- Reduced Discretionary Bias: By relying on defined metrics, the system aims to minimize subjective decision-making in the allocation of scarce resources, fostering a perception of fairness among applicants.

-

Leveraging External Funding Opportunities:

- Compliance for Collaboration: Adherence to federal income requirements is often a prerequisite for tribal nations to access and leverage additional funding streams, such as LIHTC, USDA Rural Development loans, and other state or private grants. This compliance opens doors to a broader array of development opportunities.

- Building Partnerships: Meeting federal standards demonstrates capacity and reliability, making tribal housing authorities more attractive partners for external agencies and developers.

-

Empowerment of Tribal Housing Authorities (under NAHASDA):

- Local Adaptation: NAHASDA specifically grants tribes the flexibility to define their own income limits, provided they align with the general intent of serving low-income families. This allows THAs to tailor requirements to their unique economic realities, cost of living, and cultural considerations, enhancing self-determination.

- Community-Specific Solutions: This flexibility means a tribe can choose to focus on specific segments of their low-income population, or account for unique income streams prevalent in their community, offering a more responsive "product" for their specific "users."

Cons: Design Flaws and Performance Limitations

Despite its laudable goals, the current "product" of income requirements is far from perfect, exhibiting several significant design flaws and performance limitations that hinder its effectiveness and create unintended consequences for tribal communities.

-

The "One-Size-Fits-All" Flaw and AMI Disconnect:

- Inadequate Reflection of Rural Poverty: Area Median Income (AMI), often based on county or metropolitan data, frequently fails to accurately reflect the economic realities of remote tribal lands. These areas often have significantly higher costs of living (due to transportation, limited retail options) alongside lower average incomes, making the federal thresholds artificially high for many genuinely needy families.

- Exclusion of the "Working Poor": Individuals earning just above the low-income threshold may still be unable to afford market-rate housing in their communities, but are deemed ineligible for assistance. This creates a "missing middle" – people who are too "rich" for assistance but too "poor" for the market.

- Geographic Disparities: An AMI of $50,000 might mean very different things in a bustling city versus a remote reservation with limited employment opportunities and high utility costs. The system struggles to account for these nuances.

-

The "Cliff Effect" and Disincentive to Earn More:

- Poverty Trap: A critical design flaw is the "cliff effect," where a small increase in income can lead to a complete loss of housing assistance benefits. For example, earning an extra few hundred dollars a month might push a family just over the 80% AMI threshold, resulting in the loss of thousands of dollars in housing subsidies.

- Stifling Upward Mobility: This creates a powerful disincentive for tribal members to seek higher-paying jobs, work more hours, or pursue education, as the net financial gain might be negligible or even negative. It inadvertently penalizes self-sufficiency and perpetuates reliance on assistance.

-

Administrative Burden and Complexity:

- Resource-Intensive Verification: THAs face immense administrative burdens in verifying income, which can involve collecting pay stubs, bank statements, tax returns, and other sensitive financial documents. This process is time-consuming, intrusive, and requires specialized training for staff.

- Privacy Concerns: The extensive documentation required can feel intrusive to applicants, raising privacy concerns and potentially deterring some from applying.

- Frequent Recertification: Annual or semi-annual recertification processes add to the administrative load for both THAs and residents, especially for those with fluctuating incomes from seasonal work or informal economies.

-

Exclusion of Non-Traditional Income/Assets:

- Cultural Disconnect: Some federal definitions of income and assets may not fully account for traditional economies, cultural practices (e.g., subsistence harvesting, informal bartering), or communal resource sharing prevalent in tribal communities.

- Asset Limitations: Strict asset limits can penalize families who have modest savings or traditional land holdings, even if their cash income is low.

-

Data Lag and Responsiveness:

- Outdated AMI Data: The calculation of AMI often relies on data that is several years old, meaning it may not accurately reflect current economic conditions, especially in rapidly changing or economically volatile tribal areas. This lag can result in income limits that are out of sync with present-day needs.

- Slow Adjustment: The process for updating and adjusting these thresholds can be slow and bureaucratic, failing to respond quickly to economic downturns or spikes in local cost of living.

-

Impact on Workforce Development and Community Diversity:

- Difficulty Attracting Professionals: Strict low-income requirements mean that housing assistance is generally unavailable for teachers, healthcare workers, law enforcement, or other middle-income professionals who are vital for tribal community development. This makes it challenging for tribes to attract and retain a diverse workforce.

- Homogenous Communities: An over-reliance on purely low-income housing can inadvertently create communities lacking income diversity, which can have broader socio-economic implications.

Recommendation: Optimizing the "Product" for Enhanced Performance

To transform the current system of income requirements into a more effective, equitable, and sustainable "product" for tribal housing, a multi-faceted approach is necessary, blending policy adjustments with increased investment and a focus on tribal sovereignty. Our "purchasing recommendation" is not to abandon the product entirely, but to implement critical upgrades and feature enhancements.

-

Enhance Tribal Flexibility and Local Control:

- Tailored AMI Calculations: Grant tribes greater authority to develop their own localized AMI calculations that more accurately reflect their specific cost of living, unique economic conditions, and access to resources. This could involve using a localized cost-of-living index rather than broader county-level data.

- Broader Income Bands: Allow tribes to define broader income bands for specific programs, acknowledging the "missing middle" and providing support for those slightly above traditional low-income thresholds but still in need.

- Expanded Definition of "Low Income": Provide flexibility for tribes to incorporate traditional income sources, informal economies, and unique asset structures into their eligibility criteria, ensuring cultural relevance.

-

Mitigate the "Cliff Effect" with Graduated Assistance:

- Phased-Out Subsidies: Implement a system of gradually reduced housing subsidies as income increases, rather than an abrupt termination. This could involve a sliding scale where the tenant’s share of rent increases incrementally with income, providing a smoother transition and encouraging upward mobility without penalizing success.

- Workforce Development Incentives: Integrate housing assistance with workforce development programs, allowing for temporary waivers or extended assistance periods for individuals actively pursuing education or job training that leads to higher income.

-

Streamline Administrative Processes and Reduce Burden:

- Digital Transformation: Invest in modern, user-friendly digital platforms for application and income verification, reducing paperwork and administrative time for both applicants and THA staff.

- Interagency Data Sharing: Explore secure data-sharing agreements between federal agencies (e.g., HUD, IRS, Social Security Administration) with appropriate consent, to simplify income verification and reduce the burden on applicants to repeatedly provide documentation.

- Self-Certification (with Audits): For some programs or during specific periods, allow for a higher degree of self-certification of income with robust audit mechanisms, freeing up THA resources.

-

Invest in Capacity Building for THAs:

- Training and Technical Assistance: Provide increased funding for training and technical assistance for THA staff on complex income calculations, compliance, and best practices in administering housing programs.

- Increased Administrative Funding: Recognize that administering these complex programs requires significant resources. Increase the administrative portion of IHBG and other grants to ensure THAs have the staff and tools necessary to manage the process effectively.

-

Promote a Holistic Approach to Housing Development:

- Mixed-Income Housing: Encourage and fund the development of mixed-income housing communities on tribal lands, which can cater to a wider range of tribal members, including essential service providers, thereby fostering more vibrant and sustainable communities.

- Integration with Economic Development: Link housing assistance strategies with broader tribal economic development initiatives. Stable housing is a prerequisite for a stable workforce, and housing policies should support, not hinder, economic growth.

-

Advocacy for Increased and Sustainable Funding:

- Adequate Funding Levels: Ultimately, the limitations of income requirements are often exacerbated by chronic underfunding. Sustained, robust increases in IHBG and other tribal housing programs would reduce the intense competition for limited resources, allowing for greater flexibility and broader eligibility.

- Inflation Adjustment: Ensure that funding levels for housing assistance are regularly adjusted for inflation and the rising cost of construction and living.

Conclusion: A Foundation Built on Equity and Self-Determination

The "product" of income requirements for tribal housing assistance, while serving a vital role in targeting need and ensuring fiscal responsibility, exhibits significant design flaws that can inadvertently perpetuate cycles of poverty and hinder tribal self-determination. The current system often fails to account for the unique economic, geographic, and cultural realities of Indigenous communities, creating "cliff effects" that penalize success and administrative burdens that strain already limited tribal resources.

Our review concludes that while income requirements are an indispensable component of any social assistance program, their current iteration for tribal housing is in dire need of an upgrade. The "recommendation" is clear: move towards a more flexible, culturally responsive, and user-centric system that empowers tribal nations to define their own pathways to housing stability. By investing in tribal capacity, implementing graduated assistance models, streamlining processes, and advocating for increased and sustained funding, we can transform these requirements from a barrier into a true foundation for thriving, self-determined tribal communities. Only then can the promise of safe, affordable, and dignified housing become a reality for all Indigenous peoples.