Sovereign Nation Loans for Emergencies: A Professional Step-by-Step Guide

I. Introduction: Navigating the Lifelines in Times of Crisis

Sovereign nations, like individuals, can face unforeseen emergencies that threaten their stability, economy, and the well-being of their citizens. From devastating natural disasters and public health crises to sudden economic shocks and humanitarian catastrophes, these events often overwhelm domestic resources, necessitating external financial assistance. Sovereign nation loans for emergencies serve as critical lifelines, providing the necessary capital to respond, recover, and rebuild.

However, securing such loans is a complex, multi-faceted process, fraught with diplomatic, economic, and political considerations. This professional guide aims to demystify this intricate landscape, offering a step-by-step tutorial for policymakers, government officials, and stakeholders involved in navigating the process of obtaining emergency financing from international and bilateral sources. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for any nation seeking to enhance its resilience and secure its future in an unpredictable world.

II. Understanding the Landscape of Emergency Financing

Before delving into the step-by-step process, it’s essential to grasp the fundamental elements of emergency financing for sovereign nations.

A. What Constitutes an “Emergency”?

For the purpose of sovereign emergency loans, an “emergency” typically refers to a sudden, severe, and widespread event that causes significant economic disruption, loss of life, or damage to infrastructure, and exceeds a nation’s immediate capacity to respond. These can include:

-

- Natural Disasters: Earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, droughts, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions.

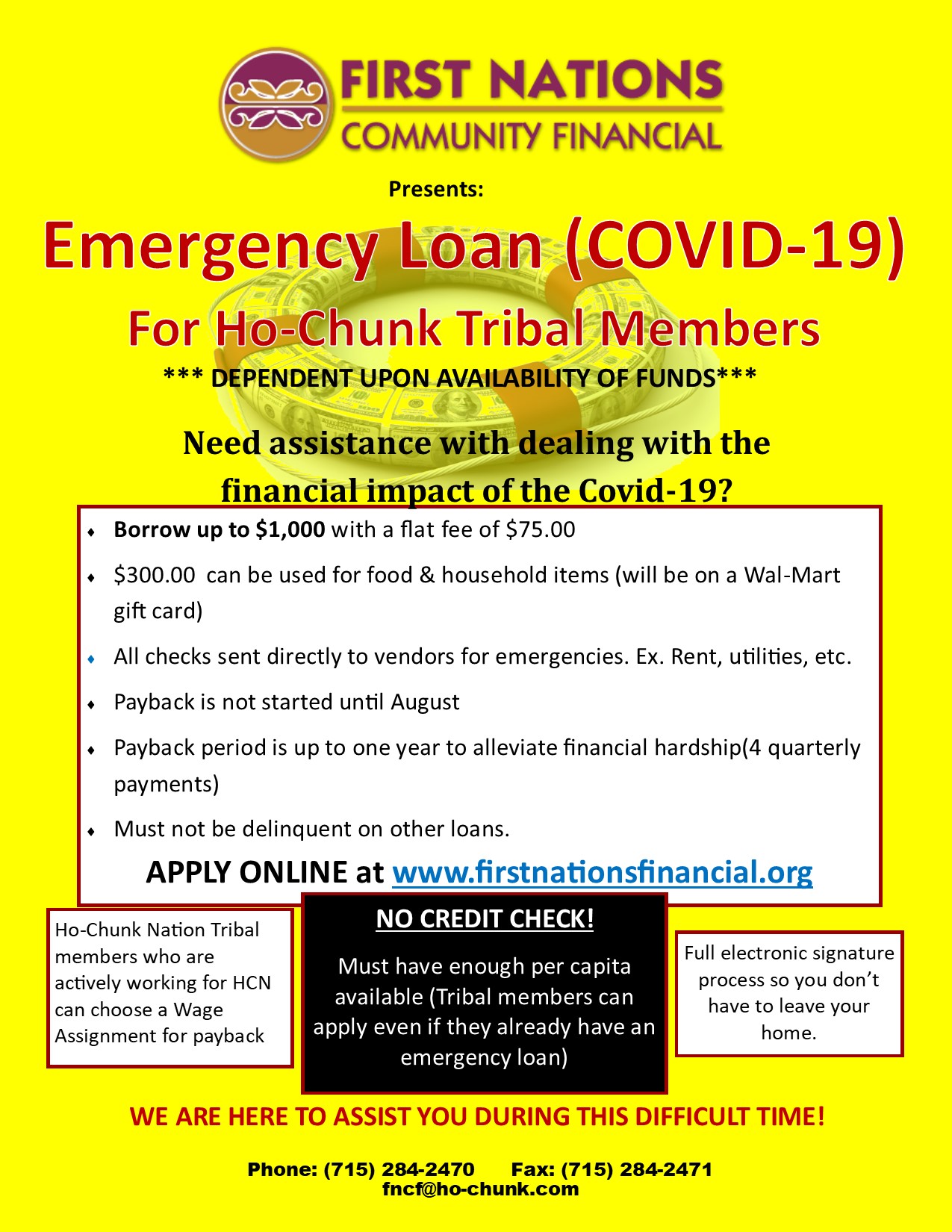

- Public Health Crises: Pandemics (e.g., COVID-19), widespread epidemics (e.g., Ebola, Zika), major health system collapses.

- Economic Crises: Sudden balance-of-payments crises, severe commodity price shocks, financial market collapses, hyperinflation.

- Humanitarian Crises: Large-scale displacement of populations, food insecurity, or famine, often exacerbated by conflict or natural disaster.

- Security-Related Crises: Though less direct, the economic and social fallout from significant security threats or conflicts can trigger emergency loan needs.

B. Primary Sources of Emergency Loans

Several international and bilateral entities serve as primary lenders for sovereign nations in emergencies, each with distinct mandates, facilities, and conditionalities.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF):

- Mandate: To ensure the stability of the international monetary system, primarily by providing short-to-medium-term financial assistance to countries facing balance-of-payments problems.

- Emergency Facilities:

- Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI): Provides rapid financial assistance to members facing urgent balance-of-payments needs, without the need for a full-fledged program or ex-ante conditionality.

- Rapid Credit Facility (RCF): Similar to RFI but for low-income countries (LICs), offering concessional terms.

- Stand-By Arrangements (SBA) / Extended Fund Facility (EFF): More comprehensive programs for deeper, structural issues, which can be adapted or accelerated in emergency contexts.

- World Bank Group (WBG):

- Mandate: To reduce poverty and support development, focusing on long-term structural reforms and project financing.

- Emergency Facilities:

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) / International Development Association (IDA): Provide loans and grants for reconstruction, recovery, and development projects. IDA offers highly concessional terms to the poorest countries.

- Catastrophe Deferred Drawdown Option (Cat DDO): A pre-arranged contingent credit line that provides rapid financing after a natural disaster.

- Emergency Recovery Lending: Specific lending operations designed to support post-disaster or post-conflict recovery and reconstruction.

- Regional Development Banks (RDBs):

- Examples: Asian Development Bank (ADB), African Development Bank (AfDB), Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

- Mandate: Similar to the World Bank but focused on specific regions, providing development and emergency financing tailored to regional needs. They often have dedicated emergency windows or rapid response facilities.

- Bilateral Lenders:

- Description: Loans provided directly from one sovereign nation’s government to another. These can be driven by geopolitical interests, historical ties, or humanitarian concerns.

- Characteristics: Terms can vary widely, from highly concessional to commercial rates. Often involve specific project ties or procurement conditions.

- Private Capital Markets:

- Description: While less common for immediate, urgent emergency response, nations with strong credit ratings may access private markets (e.g., issuing emergency bonds) for broader post-crisis recovery or to bridge financing gaps. This typically requires more lead time and a stable financial environment.

III. The Step-by-Step Process for Securing Emergency Loans

Obtaining an emergency loan is a structured, often high-pressure process. The following steps outline the typical progression:

Step 1: Initial Assessment and Needs Analysis

The first and most critical step is for the affected nation to conduct a rapid yet comprehensive assessment of the emergency’s impact and the resulting financial needs.

- Impact Assessment: Quantify the human, social, and economic damage. This includes loss of life, displacement, infrastructure damage (e.g., roads, hospitals, schools), agricultural losses, disruption to critical services, and macroeconomic implications (e.g., balance of payments, fiscal deficit, GDP contraction).

- Needs Identification: Determine immediate humanitarian needs (food, shelter, medical aid), short-term recovery requirements (debris removal, temporary housing), and medium-to-long-term reconstruction and resilience-building needs.

- Financial Gap Analysis: Estimate the total cost of response and recovery, and compare it against available domestic resources (e.g., emergency reserves, budget reallocation, domestic borrowing capacity). The resulting deficit defines the emergency financing requirement.

- Urgency Assessment: Prioritize needs based on criticality and timeliness, distinguishing between immediate cash flow needs and longer-term project financing.

Step 2: Identifying Potential Lenders and Eligibility

Based on the needs analysis, the borrowing nation must strategically identify the most appropriate lenders.

- Match Crisis Type to Lender Mandate:

- For immediate balance-of-payments support, the IMF (RFI/RCF) is often the first port of call.

- For reconstruction and infrastructure, the World Bank and RDBs are key.

- For specific humanitarian aid, UN agencies or bilateral partners might be more direct.

- Review Eligibility Criteria: Each institution has specific membership requirements, income thresholds (e.g., IDA for low-income countries), and track records of economic management that influence eligibility for certain facilities.

- Leverage Existing Relationships: Countries with established relationships and ongoing programs with the IMF, World Bank, or RDBs may find it easier to activate emergency facilities or adapt existing programs.

- Consultation: Engage informally with resident representatives or country desks of potential lenders to gauge interest and suitability.

Step 3: Formal Application and Engagement

Once potential lenders are identified, the formal process begins.

- Official Request/Letter of Intent (LOI): The borrowing nation’s government (typically the Ministry of Finance or Central Bank) submits a formal request for assistance. For the IMF, this often takes the form of an LOI, outlining the government’s understanding of the crisis, its proposed policy response, and the requested financing.

- Documentation Submission: Provide detailed supporting documents, including the impact assessment, financial gap analysis, proposed emergency response plan, macroeconomic data, and fiscal projections.

- High-Level Dialogue: Engage in intensive discussions with lender delegations (e.g., IMF missions, World Bank teams). These discussions will verify the assessment, evaluate the proposed policy response, and identify potential areas for conditionality.

Step 4: Negotiation of Terms and Conditions

This is often the most sensitive phase, where the specifics of the loan agreement are hammered out.

- Loan Amount: Negotiate the total volume of financing, which is typically capped by the lender’s exposure limits, the nation’s quota (for IMF), or the severity of the crisis.

- Interest Rates and Repayment Schedule: Discuss the interest rate (often concessional for emergency loans), grace periods, and the overall maturity of the loan. For concessional lenders like IDA or RCF, these terms are highly favorable.

- Conditionality (Policy Reforms): This is a cornerstone, especially for IMF and World Bank loans. Lenders typically impose policy conditions designed to address the root causes of the crisis, ensure the effective use of funds, and promote long-term stability. These can include:

- Macroeconomic Stability: Fiscal consolidation, monetary policy adjustments, exchange rate management.

- Structural Reforms: Governance improvements, anti-corruption measures, public financial management reforms, sectoral policies (e.g., energy, health).

- Transparency and Accountability: Reporting requirements on fund utilization.

- Negotiations aim to find a balance between the lender’s requirements for sound policy and the borrowing nation’s sovereignty and political feasibility.

- Disbursement Modalities: Agree on how and when funds will be released (e.g., immediate single tranche, multiple tranches tied to policy actions).

Step 5: Approval and Legal Formalities

Following successful negotiations, the proposed loan agreement must undergo formal approval.

- Lender Board Approval: The Executive Board of the IMF, World Bank, or RDB reviews the staff-level agreement and formally approves the loan.

- Borrowing Nation’s Internal Approval: The loan agreement must typically be approved by the borrowing nation’s relevant legislative body (e.g., Parliament, National Assembly) to ensure legal validity and national ownership.

- Signing of Agreements: Once all approvals are secured, the loan agreement and any associated memoranda of understanding are formally signed by authorized representatives of both parties.

Step 6: Disbursement of Funds

Upon completion of legal formalities, the funds are disbursed.

- Immediate vs. Tranche-Based: Emergency loans, particularly those from the IMF’s RFI/RCF, are often disbursed quickly and in full or in large initial tranches to address immediate needs. More comprehensive programs (SBA, EFF, WB project loans) typically disburse funds in tranches, contingent upon the borrowing nation meeting agreed-upon policy actions or performance criteria.

- Mechanism: Funds are usually transferred directly to the central bank of the borrowing nation.

Step 7: Implementation, Monitoring, and Reporting

The borrowing nation is responsible for implementing the agreed-upon policies and utilizing the funds effectively.

- Policy Implementation: Execute the macroeconomic and structural reforms agreed upon during negotiations.

- Fund Utilization: Ensure the funds are spent transparently and efficiently on the intended emergency response and recovery efforts.

- Monitoring and Reporting: Regularly report to the lending institution on economic performance, policy implementation, and the use of funds. Lenders conduct periodic reviews to assess progress and compliance with conditionalities. Technical assistance is often provided by lenders to support implementation capacity.

- Auditing: Independent audits of fund utilization are often required to ensure accountability and prevent corruption.

Step 8: Repayment

Adherence to the repayment schedule is crucial for maintaining the nation’s creditworthiness and access to future financing.

- Scheduled Payments: Make principal and interest payments according to the agreed-upon schedule.

- Debt Management: Proactive debt management strategies are essential to ensure long-term debt sustainability, especially after taking on emergency loans.

- Consequences of Default: Failure to repay can lead to severe consequences, including damaged international reputation, inability to access future credit, and potential legal action.

IV. Key Considerations and Challenges

Securing and managing emergency loans presents several critical considerations and challenges:

A. Urgency vs. Due Diligence

The need for rapid response often conflicts with the requirement for thorough assessment and due diligence. Lenders aim to streamline processes for emergencies (e.g., RFI), but borrowing nations must still provide sufficient data to justify the loan.

B. Conditionality and Sovereignty

The policy conditions attached to loans, particularly from the IMF and World Bank, can be politically sensitive. Balancing the need for external financing with national sovereignty and domestic political realities requires careful negotiation and communication.

C. Debt Sustainability

While necessary, emergency loans add to a nation’s debt burden. It is paramount to ensure that the additional debt does not push the country into an unsustainable debt trap, hindering future development. Long-term debt management and sustainability analysis are crucial.

D. Transparency and Governance

Ensuring that emergency funds are used for their intended purpose and not diverted through corruption is a major challenge. Lenders increasingly emphasize strong governance, transparency, and anti-corruption measures as part of loan conditionalities.

E. Political Will and Domestic Consensus

Implementing often difficult policy reforms and ensuring the effective use of funds requires strong political will and broad domestic consensus. Without these, even well-designed loan programs can falter.

F. Capacity Constraints

Many nations facing emergencies may have limited technical and administrative capacity to rapidly assess needs, negotiate complex loan agreements, and implement stringent reporting requirements. Lenders often provide technical assistance to mitigate this.

V. Conclusion: Building Resilience Through Strategic Financing

Sovereign nation loans for emergencies are indispensable tools for countries grappling with unforeseen crises. They provide the vital financial resources to save lives, restore stability, and lay the groundwork for recovery and reconstruction. However, securing these lifelines is a sophisticated process demanding strategic planning, robust internal governance, transparent execution, and skillful negotiation with international partners.

By meticulously following the steps outlined in this guide and proactively addressing the inherent challenges, sovereign nations can effectively leverage emergency financing to mitigate the impact of crises, strengthen their resilience, and safeguard their path towards sustainable development. The ability to navigate this complex financial landscape is a hallmark of responsible governance and a cornerstone of national stability in an increasingly volatile world.